A second setback in the trade war, after the escalation with China

Link

Read Xavier Chapard's market analysis for April 14, 2025.

Summary

► A second setback in the US tariff war took place this weekend with the exclusion of consumer electronics goods from the tariff hikes, even on Chinese goods (and therefore iPhones). 12% of US imports are not taxed further, ¼ of which comes from China.

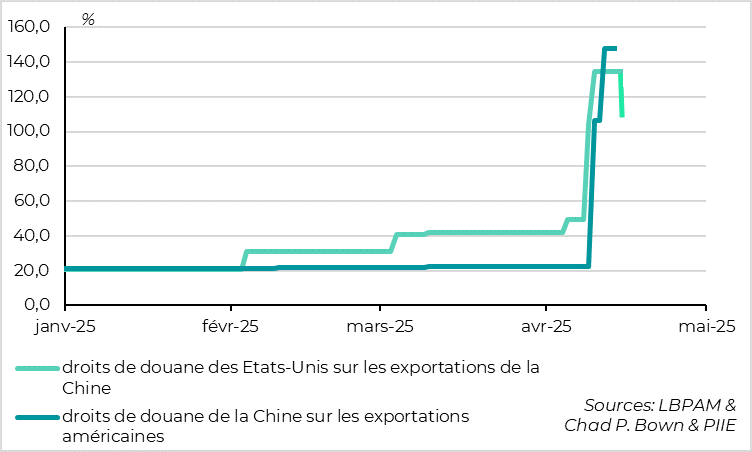

► However, this follows an escalation of tariffs between the US and China with mutual retaliation. US tariffs on Chinese goods have been raised to 145%, while China has retaliated by increasing its tariffs on US goods to 125%. At this stage, the exact level of tariffs on overtaxed goods no longer makes much economic sense, since most bilateral trade in these goods has already been discouraged.

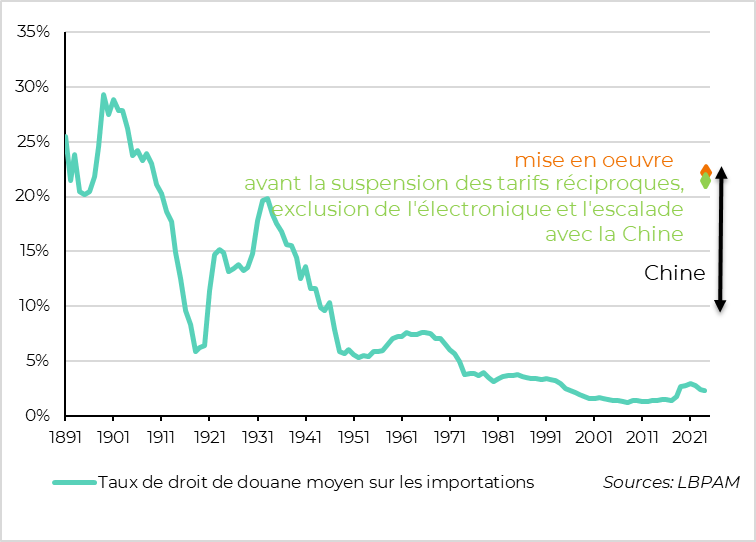

► As a result of this escalation, the increase in the average tariff applied by the USA (almost 20%) exceeds that announced on the day of release (i.e. before the suspensions on the number of countries and on electronic goods), but the distribution of the increases is different and therefore the economic impact of the trade war a little less extreme. Indeed, 2/3 of the average tariff increase reflects those applied to China, while the rest of the world's tariff increase is just under 10%.

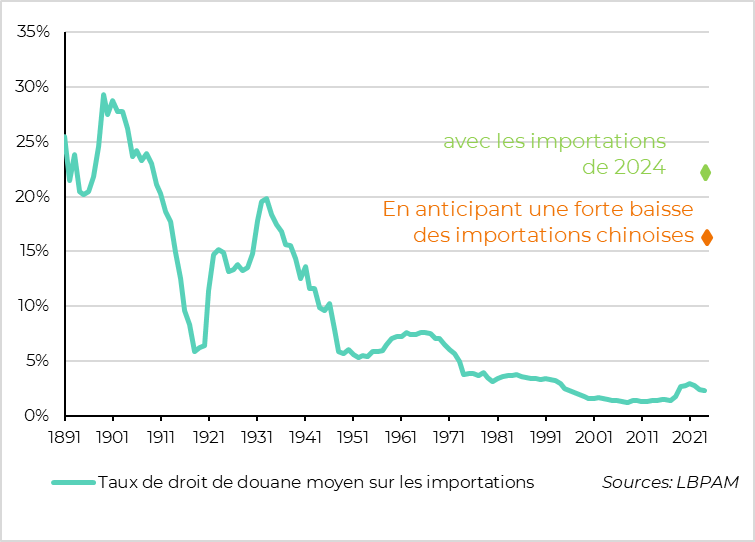

► Taking into account the likely fall in China's weight in US imports, we estimate that the increase in tariffs is likely to be around 15% this year. This somewhat reduces the stagflationary impact, which remains very significant, and also reduces the tax revenues that the US Treasury can expect.

► US fiscal room for manoeuvre is further reduced by the fact that the market seems to be questioning the safe-haven status of US debt, judging by the sharp rise in US yields in recent weeks.

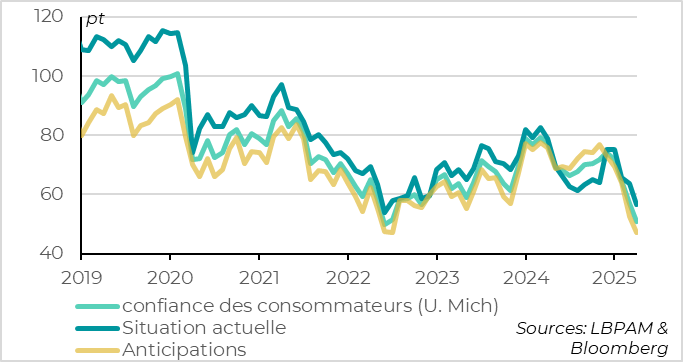

► Despite the White House's backtracking, some of the negative impact of the trade war on the US economy is already taking place. US consumer confidence continues to fall in early April, and household inflation expectations are rising to their highest levels in decades. This should prompt the Fed to remain cautious, despite downward surprises for consumer and producer prices in March.

► UK GDP rose by 0.5% in February, indicating an acceleration in growth ahead of the shock of the trade war and April's tax and regulated price hikes. This is encouraging, even if growth is expected to slow sharply in Q2, especially as uncertainty and financial conditions have deteriorated since the beginning of the month.

To do deeper

USA-China: even escalation in the face of China has a high limit

The escalating tariff war between the USA and China seems to have reached its peak, but at a very high tariff level following the cycle of retaliation after retaliation.

The US reported that tariffs on Chinese goods were in fact 145% versus 125% announced, as they had forgotten to count the 20% imposed as part of the fight against Fentanyl in February and March. This prompted the Chinese to increase their tariffs on US goods from 84% to 125%.

Both parties finally admitted that there was no point in continuing to raise these taxes any further, given the levels reached, which should already discourage most bilateral trade in goods.

This weekend, under pressure from Big Tech, D. Trump even backed down again, excluding consumer electronics goods such as IPhones from reciprocal tariffs for all countries, but also from retaliatory tariffs on China (but not from the 20% already imposed on China in February and March). This is a significant setback, since these goods account for 12% of US imports, and more than a quarter of them come from China. This reduces the tariff on US imports by 1 percentage point, and those on Chinese goods by almost 30 points (while leaving them above 100%).

The fact remains that, after the extreme escalation of tariffs between China and the USA, it is now necessary to treat China separately in order to judge the impact of US tariff policy on the economy.

United States: escalation on China masks partial retreat on the rest of the world

Indeed, a crude calculation implies that in the current situation, the average customs duties applied by the United States are up by almost 20% compared to the start of the year. That's as much as was calculated before the White House backtracked (i.e. the suspension of reciprocal tariffs above 10% for some sixty countries and the exclusion of electronic goods), and before the China-US escalation.

But the breakdown of tariff increases is now quite different, with 2/3 of the increase coming solely from the extreme tariffs applied to China, whereas Chinese goods accounted for “only” 13% of US imports last year. The increase in tariffs for the world outside China averages just under 10%, which is very substantial, but 6 points below the reciprocal tariffs announced on Release Day.

The problem with estimating the average tariff rate is that we use the weight of each country in US imports during the year under analysis. But for 2025, we use the weights of the previous year, 2024, since we don't yet know the imports for 2025. When tariff increases are limited or similar between trading partners, this approximation does not skew the result too much.

United States: the tariff hike will be slightly less extreme than current calculations suggest

But when tariff increases differ greatly between countries, as is currently the case between China and the rest of the world, it is certain that there will be a reorganization of trade flows and that China's weight in American imports will fall sharply this year. Chinese goods will be replaced by goods from other countries, and Chinese exports will pass through other countries.

As a result, the average tariff rate calculated with 2025 import weights will be much lower than that currently calculated with 2024 imports. Assuming that China's weight in US imports will fall by 2/3, we arrive at a tariff increase of just under 15% instead of the 20% currently calculated.

This is a massive shock, but below the estimates made on “Liberation Day” (i.e. before the suspension of additional reciprocal tariffs). This implies that the stagflationary impact will be somewhat less massive than with a real 20% increase in US tariffs, but also that the budgetary revenues for the US Treasury will be lower than the $800bn announced (probably of the order of a third according to our estimates).

While the uncertainties are massive on both the upside and the downside, we retain a central scenario in which the US flirts with recession in the remainder of the year, but avoids entering a full-blown recession.

On the other hand, budgetary margins look tight. We always thought that tariff revenues (probably less than 1% of GDP) would be far from offsetting the extension of the 2017 tax cuts (more than 1pt of GDP per year) and the new tax cuts proposed by Congress (0.5pt of GDP).

Fiscal room for manoeuvre is all the more reduced when we see the reaction of US long rates since the beginning of the month, which are rising despite the worsening economic outlook, Fed rate cut expectations and rising risk aversion. This suggests that the US Treasury's exorbitant privilege (i.e. to borrow at low rates when risks are rising, with no impact on the fiscal outlook) is being called into question by investors.

United States: consumer confidence continues to plummet in early April

US consumer confidence continues to fall in early April, according to the University of Michigan's preliminary survey, reaching its second lowest level in history.

Once again, questions on household prospects are the most negative, with the expectations indicator reaching its lowest level since the early 1980s. But unlike previous surveys, questions on the current situation of households are also starting to fall sharply. This is a bad sign, as the current household situation indicator is less volatile and has historically been the best indicator for identifying changes in economic trends.

United States: household inflation expectations rise again

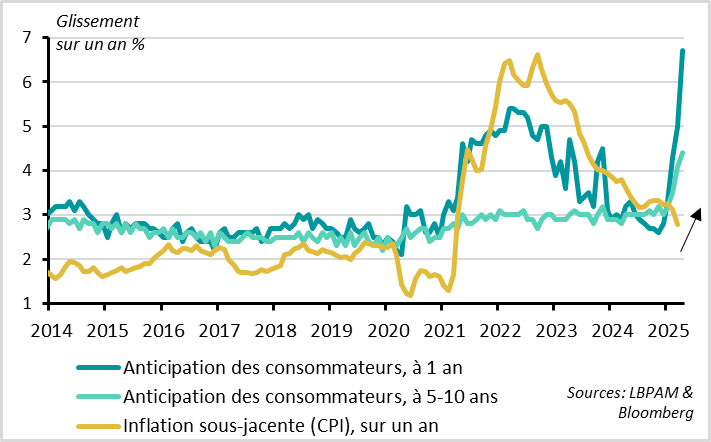

Household inflation expectations continue to rise to very high levels according to the survey, in both the short and long term.

One-year inflation expectations have jumped by 1.7 percentage points to 6.7%, surpassing the high points of the 2021-22 inflation shock and reaching their highest level since the early 1980s. Above all, long-term inflation expectations (5-10 years), which had remained anchored during the recent inflationary shock, rise by a further 0.3 percentage points to 4.4%. These long-term expectations, which are closely monitored by the Fed, are at their highest level since 1991.

The University of Michigan survey still reveals historic discrepancies between the responses of households supporting Democrats and those supporting Republicans, but the direction is now the same for all households. They all indicate a drop in confidence and a rise in inflation fears, even if the levels remain very different.

We think this is more important for the Fed than the good inflation figures for March (i.e. the slowdown in consumer and producer prices). Indeed, the March price figures do not yet reveal the impact of tariffs, which should start to push up goods prices sharply in the coming months. And it is the firm anchoring of inflation expectations that will determine whether or not the tariff shock can be considered transitory, and thus whether or not the Fed will have the leeway to defend its employment mandate.

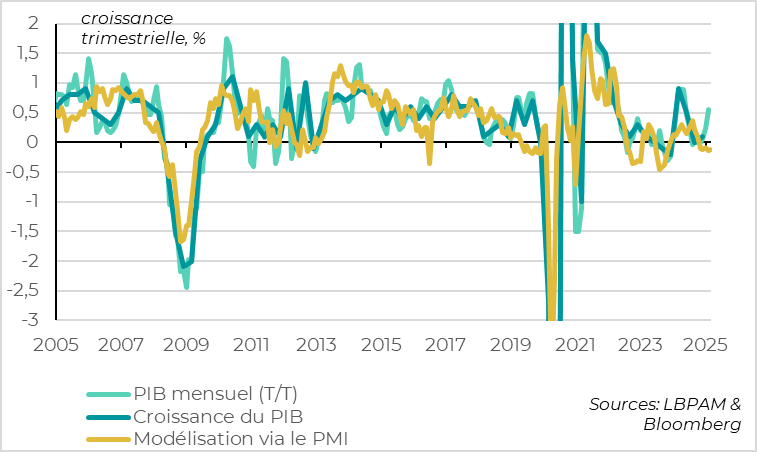

United Kingdom: growth surprises positively in early 2025, but may not be sustainable

UK GDP rose by 0.5% in February, after being revised from -0.1% to 0.0% for January. This leaves a growth assumption of 0.5% for Q1, which would be a net acceleration after the UK's near-zero growth in H2 2024. What's more, while the rise in activity in March is exaggerated by the 2.2% rebound in manufacturing activity, it is fairly widespread (+0.3% for activity in services).

This is yet another sign that activity in Europe was improving at the start of the year, before the shock of the trade war. That said, it probably reflects in part the advance of industrial activity in anticipation of the US tariff hikes. And in the case of the UK, activity in all sectors also advanced in Q1 ahead of the rise in payroll taxes and energy bills in April.

With the backlash of these effects in Q2, in addition to the effective increase in US tariffs (10% for the UK), heightened uncertainty and worsening financial conditions, activity will slow in Q2, and the question is whether it will be able to avoid contracting. This will depend on the duration and extent of trade and financial uncertainty, and will need to be closely monitored in the data over the coming weeks.

Xavier Chapard

Strategist