As long as the economy holds, markets follow

Link

In spite of mounting geopolitical tensions and the uncertainty generated by the sometimes unorthodox orientations of the U.S. administration, financial markets continue to advance in early 2026. While this situation may appear paradoxical, it is ultimately less so in the eyes of Xavier Chapard. Find out more in our January 16, 2026 market analysis.

Overview

► Despite rising geopolitical risks (Venezuela, Greenland and, most notably, Iran) and the uncertainty created by the heterodox policies promoted by the U.S. government (in areas such as real estate, credit cards and the independence of the Federal Reserve), markets remain on an upward trend at the start of the year. This may seem paradoxical, but in our view, it is not as surprising as it appears.

►First, geopolitical shocks have so far not altered the central scenario, and their evolution remains highly unpredictable. Admittedly, tensions in Iran have pushed oil prices higher, but only marginally. Markets tend to struggle to price geopolitical risk as long as it does not translate into a clear economic impact (through commodities, effects on a systemic economy, etc.). Moreover, one may assume that the U.S. government would step back if the economic measures it is advocating were to have an excessively negative impact on financial markets. Of course, the situation on both fronts could deteriorate rapidly, which is why we favour a high degree of agility and continue to implement diversification and hedging strategies within our allocations.

► Above all, the macroeconomic backdrop remains supportive at the start of the year. Global growth is proving resilient and could even accelerate slightly on the back of fiscal support measures. Inflation is broadly under control, and central banks remain ready to ease policy further if necessary—particularly the Federal Reserve. In this environment, we continue to believe that risk assets can move higher despite prevailing risks.

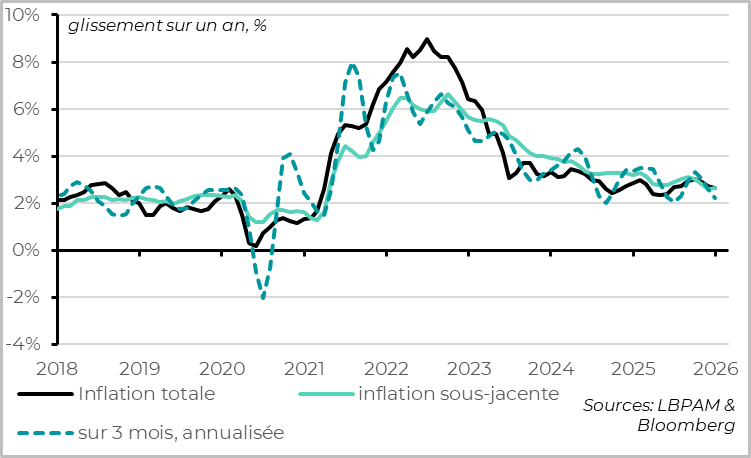

► On the data front, U.S. inflation did not rebound as much as expected in December, suggesting that the slowdown observed in October and November was not solely due to data gaps and distortions linked to the government shutdown. Inflation therefore remains steady at 2.6%, its lowest level in four years. That said, a closer look reveals surprisingly large price swings across certain goods and services even in December, making price trend interpretation in the United States still uncertain.

►Our current assessment is that inflationary pressures remain stable despite tariffs, but still somewhat elevated—closer to 3% than to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. We also believe that the Fed will wait for higher-quality data before drawing firm conclusions on the inflation trend, which likely pushes the next rate cut back to mid-year. At the very least, however, this does not call into question the still downward trajectory of Fed policy rates

►U.S. economic data remain solid. As a result, we continue to believe that the Fed will deliver only one rate cut this year. Initial jobless claims remain at their lowest levels since the start of the trade war in early 2026, pointing to a labour market that remains resilient. Retail sales also held up well in October and November despite the government shutdown (+0.4% after +0.6%). In addition, home sales reached a three-year high in December, consistent with a modest recovery in the housing market this year, supported by the decline in mortgage rates since last summer—a trend that could be further reinforced by recent government measures aimed at improving access to housing.

►In Europe, the latest activity data confirm a slight cyclical improvement at the end of 2025 following the slowdown triggered by the trade war in mid-year. UK GDP rose by 0.3% in November after falling by 0.1% in October, a welcome development given that budget uncertainty persisted until the end of November. This reduces the risk of a GDP contraction in Q4.

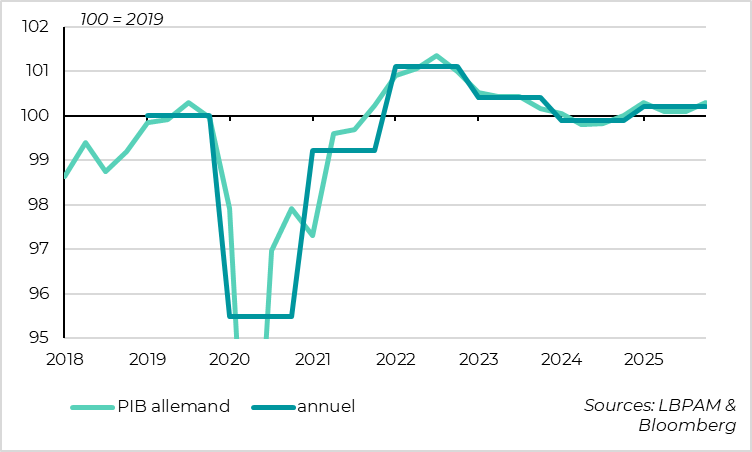

►Germany has also emerged from recession, with GDP growth of 0.3% last year after two years of contraction, although growth remains subdued. Fiscal support has been relatively limited, as the public deficit narrowed from 2.7% to 2.4% of GDP. However, as we believe that fiscal stimulus began to pick up in the final quarter of last year and should intensify in 2026, we remain constructive on Germany’s growth outlook this year—by extension supporting growth prospects across the rest of the Eurozone.

►In China, exports once again surprised to the upside at the end of 2025, confirming that they remained one of the key drivers of the Chinese economy last year despite the trade war. This is likely to remain the case in 2026 given the authorities’ strategy, although the size of China’s trade surplus—now exceeding 1% of global GDP—is prompting many governments to introduce targeted protectionist measures. Against this backdrop, we believe the authorities will further stimulate domestic demand early in the year to ensure that growth does not slow too far below the 5% target.

Going Further

United States: still no clearer picture on the inflation trend

Headline inflation returns to target, while core inflation resumes its decline in December

U.S. inflation remained stable at 2.7% in December, with consumer prices rising by 0.3% month-on-month. More importantly, core inflation (excluding food and energy) increased by “only” 0.2% over the month and was unchanged at 2.6% year-on-year. This marks its lowest level in four years and suggests that inflation is finally slowing below the 3% threshold.

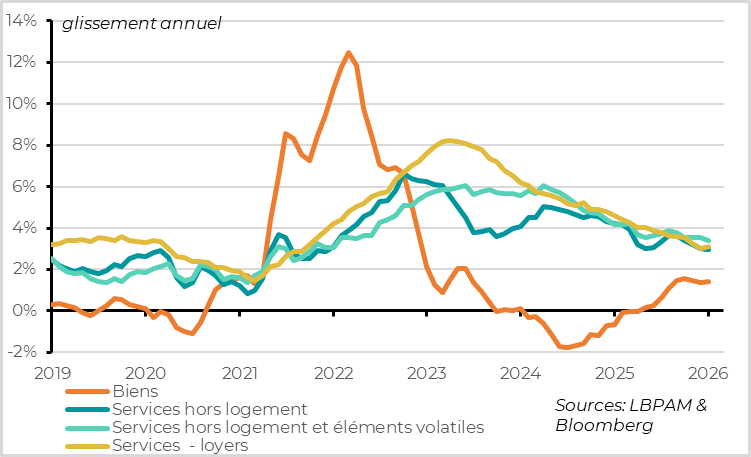

Price catch-up effects following the incomplete data releases in October and November are clearly visible. Food inflation rebounded from 2.6% to 3.1% in December, returning to its pre-shutdown level. Housing prices rose 3.1% year-on-year (+0.4% m/m) after easing to 3.0% in November (+0.15% over two months), reflecting the normalisation of the rent index and a rebound in hotel prices. Airfare prices also jumped 5.2% in December after declining by 6.6% over the previous two months.

Does this mean that inflationary pressures are now durably easing? Not necessarily.

Labour market deterioration is disproportionately affecting certain segments

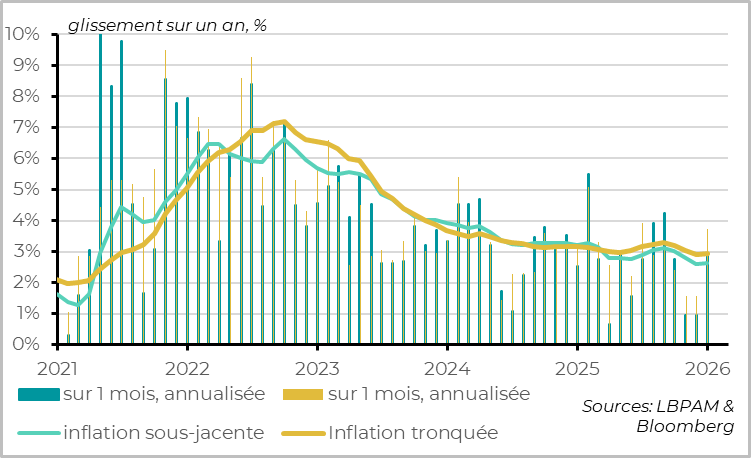

The soft inflation reading in December is once again driven by a handful of extreme price movements, suggesting that the inflation index remains distorted despite the end of the government shutdown.

Core goods prices were flat in December, as in the previous two months, largely due to the decline in used car prices (-1.1% m/m). Excluding used vehicles, core goods prices rose 0.2% in December after stagnating during the shutdown, returning to their summer pace of increase. On a year-on-year basis, core goods prices are up 1.4%, the strongest rise in two years. The pass-through of tariff increases therefore continues, albeit in a contained manner (well below the 7.7% peak reached in 2022). These prices are likely to rise further in the coming months as tariffs feed through with a lag.

The real surprise comes from core services prices excluding housing, a measure closely monitored by the Federal Reserve as it is less volatile and typically better reflects underlying domestic inflation pressures. These prices rose by just 0.2% in December, following 0.1% increases in October and November. On a year-on-year basis, they are now rising by less than 3% for the first time in four years. However, here again, the subdued reading reflects sharp declines in specific categories (-0.7% for internet subscriptions, -14% for moving services, etc.).

Unlike goods, services inflation continues to slow only gradually

Measures of underlying inflation that exclude volatile and extreme values paint a less favourable picture in December than headline core inflation, pointing to an inflation trend that remains stable and close to 3%. For instance, trimmed-mean inflation rose from 2.9% to 3.0% year-on-year, driven by the strongest monthly price increase in six months (+0.3% m/m).

Overall, December’s inflation data are reassuring in the sense that they do not show a rebound following the end of the shutdown, reducing the risk of a sharp near-term acceleration in inflation. However, the lingering distortions after the shutdown still prevent a clear reading of short-term inflation dynamics. The most likely scenario remains that underlying inflation stays around 3% and does not yet slow towards the Fed’s 2% target.

We therefore continue to believe that inflation will rise again in the first part of the year due to the ongoing pass-through of tariff increases into domestic prices, and that it will remain closer to 3% than 2% at least until next year.

Germany: the exit from recession is confirmed, but momentum remains weak at end‑2025

Survey data show a modest improvement in December

German GDP grew by 0.3% in 2025, as expected, following two years of recession that were slightly deeper than initially estimated (-0.7% in 2023 and -0.5% in 2024). Growth was driven by public and private consumption (+1.5%), which more than offset the decline in investment and net exports caused by the trade war.

Given the growth recorded over the first three quarters, this implies that GDP rose by 0.2% in Q4 after stagnating in Q3. There was therefore a modest cyclical improvement at the end of the year, even though overall growth remains subdued.

That said, GDP is only marginally above its pre‑Covid level (+0.2%) and still 1% below its level at the start of the energy shock triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Germany’s former growth model, based on cheap Russian energy and strong external demand, continues to act as a structural drag.

The public deficit narrows further in 2025

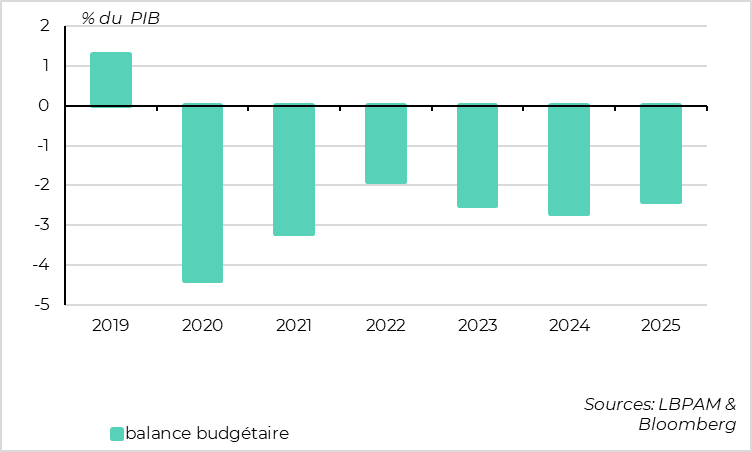

Germany’s public deficit narrowed from 2.7% to 2.4% of GDP in 2025, its lowest level since 2022. This outcome is well below consensus expectations (2.7%), the European Commission’s forecast (3%), and even further below the 2025 budget target (-3.5%), implying a gap of around €47bn. Such figures raise questions about Germany’s ability to deliver the large fiscal support announced in mid‑2025.

That said, the deficit declined sharply in the first part of the year, as the budget was only passed in September. As a result, there was a clear fiscal easing towards the end of the year, exceeding 0.5pp of GDP compared with 2024, according to our estimates. While Germany’s stimulus plan is more gradual than the federal government would like, it is nonetheless now underway.

Overall, we continue to anticipate a fiscal loosening of around 1pp of GDP in Germany this year, which is substantial—even if below the 1.5pp announced by the government. This should reinforce the cyclical recovery and allow Germany to grow by more than 1%. Given Germany’s weight in the region and the spillover effects of German investment on other economies, this will provide meaningful support to euro area growth as a whole.

China: exports continue to support growth at the end of 2025

Chinese exports remain buoyant

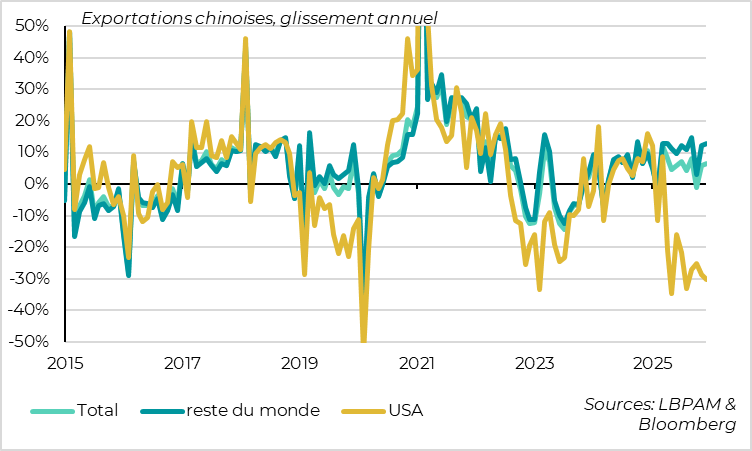

Chinese exports once again surprised to the upside in December, accelerating from 5.9% to 6.6%, bringing full‑year export growth to 5.5% in US dollars. Given ongoing price declines in China, export volumes are likely to have grown even more strongly.

Once again, the sharp contraction in exports to the United States—down 30% compared with end‑2024—has been offset by robust export momentum to the rest of the world, including Europe and emerging markets (even though part of these flows ultimately ends up in the United States). In terms of product composition, Chinese exports continue to be driven by automobiles and technology, particularly AI‑related equipment.

China’s trade surplus exceeds 1% of global GDP

Imports also picked up in December, rising from 1.9% to 5.7%, including purchases of U.S. soybeans as stipulated in the Trump–Xi agreement. Over the full year, however, imports were broadly flat.

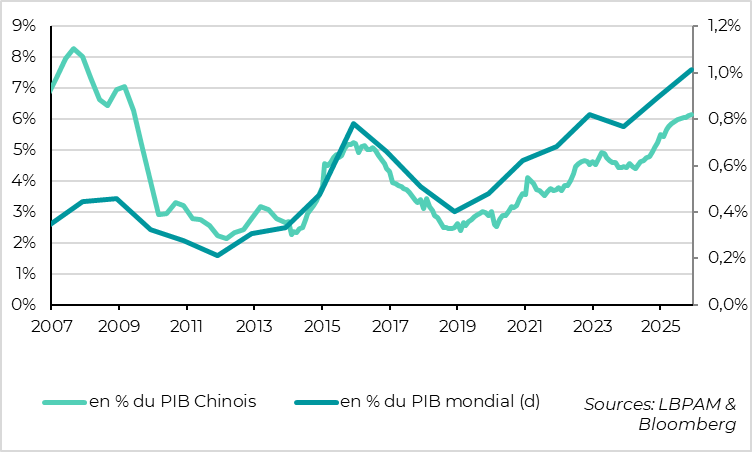

Overall, China’s trade surplus increased by USD 200bn in 2025, despite the trade war, reaching USD 1.2tn. This represents a new historical high—not as a share of Chinese GDP (it was higher before the global financial crisis), but as a share of global GDP, now exceeding 1%.

Foreign trade therefore remained one of the key drivers of Chinese growth in 2025, enabling the economy to reach its 5% growth target despite weak domestic demand. This reflects both an aggressive export‑support strategy and a continued push to onshore production of goods previously imported (excluding commodities).

Xavier Chapard

Strategist