Central bankers become (slightly) more cautious

Link

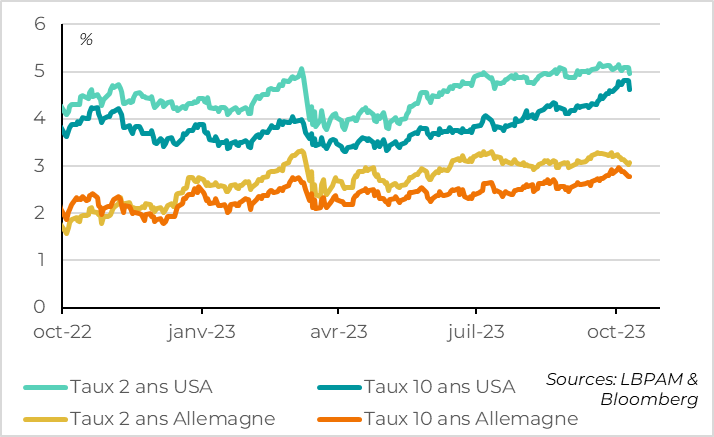

- Interest rates are finally easing slightly after their massive rise over the past 2 months. The US 2-year yield has fallen back below 5% for the first time since mid-September, and the 10-year yield has lost almost 20bp since its Friday high, dropping back to 4.6%. As a result, equity markets have stabilized and credit and dollar spreads have fallen slightly.

- Of course, the tragic events in the Middle East have helped to push yields down, as rising geopolitical uncertainties and oil risks justify a search for reserve assets such as government bonds. But this is not the main factor, in our opinion.

- This easing comes from the change in rhetoric from central bankers over the weekend, who are becoming much more cautious following the sharp rise in long rates over the past two months. For example, several Fed members have indicated that the Fed does not need to raise rates as much as it would have if financial conditions had not tightened via the market, and pointed out that the Fed announced a more cautious stance in September. On the ECB side too, some of the usually hardline members suggested that rates were high enough, and turned the debate to the speed of liquidity reduction rather than key rates.

- All in all, the change in central bankers' rhetoric is in line with our scenario of no further rate hikes between now and the end of the year for either the ECB or the Fed, even if for the latter the risk of a final hike remains significant given the resilience of the US economy. This supports our overweight position on sovereign bonds on both sides of the Atlantic.

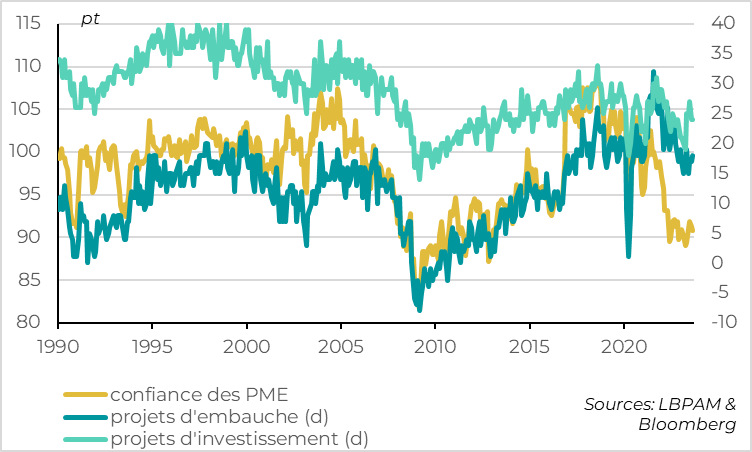

- On the data front, the NFIB's survey of SMEs confirms the resilience of the US economy and suggests that tensions on the labor market have stopped easing this summer. The question remains whether the tightening of financial conditions this summer will weigh on growth in the months ahead and ultimately reduce inflationary pressures, which is our view.

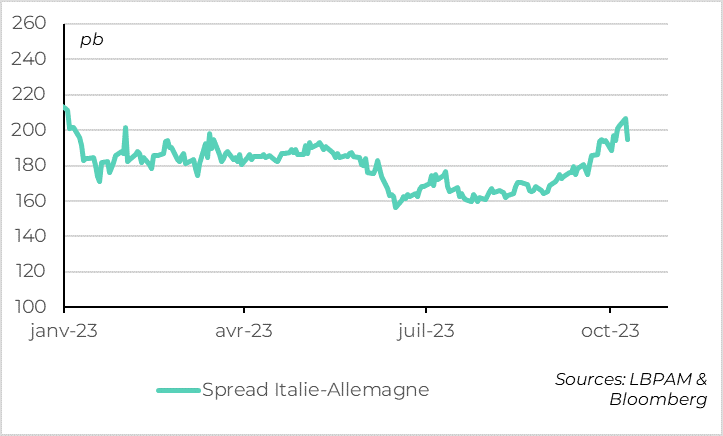

- In the Eurozone, tensions on Italian debt have eased slightly in recent days, thanks to lower long-term rates and the EU's disbursement of an 18.5 billion euro tranche of the European stimulus package that had been blocked since March. Even though interest rates should be less unfavorable to Italian debt from now on, we remain cautious on the latter, as the ECB is reducing its bond portfolio, budget negotiations for 2024 are likely to be difficult, and there are still more than 100 billion euros of European aid to be disbursed.

- The IMF's semi-annual forecast update offers few surprises. It forecasts sluggish growth, slightly stronger in the US and slightly weaker in the Eurozone and China. But what is notable is that the IMF now believes that fiscal policy has been markedly accommodative this year, especially in the US. This may go a long way towards explaining the resilience of the economy. But fiscal policies are likely to become a drag on growth again next year.

Fig.1 Markets: sovereign interest rates finally ease a little

Interest rates are finally easing slightly after several weeks of steep rises. The US 2-year yield fell back below 5% for the first time since mid-September, and the 10-year yield has lost almost 20bp since its Friday high, falling back to 4.6%. This also led to a slight easing of rates in the Eurozone, with the German 10-year rate down 10bp to below 2.8%.

Of course, the tragic events in the Middle East contributed to this movement, but this is probably not the main factor. The geopolitical uncertainty generated by the situation and the risks to the oil market (especially in relation to Iran) probably encouraged a search for safe-haven assets. But the rise in oil prices (+4 dollars per barrel to 88) and gold prices (+2% since the weekend) is limited, suggesting contained risk premiums. And the dollar has depreciated slightly and equities have risen slightly, which is not consistent with a sharp rise in risk premiums.

In our view, this mainly reflects the change in central bankers' rhetoric since the weekend, which has become markedly more cautious in response to the sharp rise in long rates over the past month.

For the Fed, San Fransico Fed President Daly said yesterday that the increases in long rates could mean that the Fed "doesn't need to do as much", adding that they "could be equivalent to another rate hike". This echoes several speeches by Fed members, including that of Fed Vice Chairman Jefferson on Monday, insisting that raising long-term rates was contributing to further tightening of financial conditions and echoing Powell's idea that the Fed can be more "cautious" now that key rates are at a clearly restrictive level and inflation is slowing.

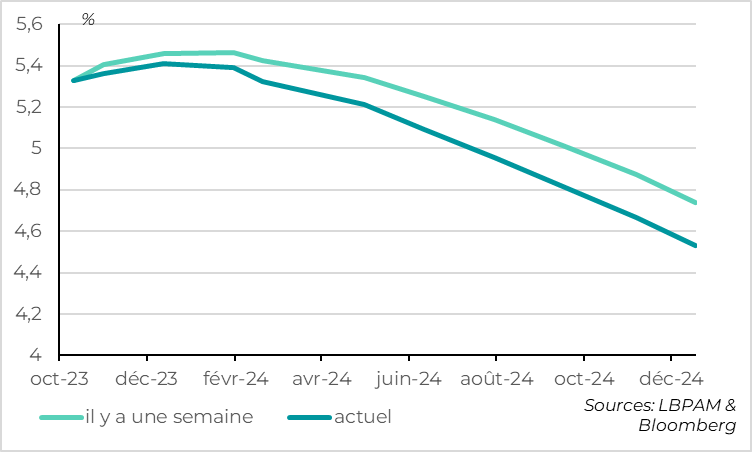

The market is pricing in a one-in-three chance that the Fed will raise rates one last time this year, compared with more than a one-in-two chance a week ago, and more than three rate cuts for next year, compared with two last week.

On the ECB side too, rhetoric is a little more cautious. For example, Dutch bank governor Knot, usually rather tough, said that rates could remain unchanged "as long as we maintain a credible inflation outlook of 2% in 2025". In fact, a majority of ECB members seem to think that the ECB doesn't need to raise rates any further, and internal debates seem to be focusing more on how to reduce excess liquidity more quickly (and in our opinion, above all, to reduce the cost to the ECB of remunerating banks' excess reserves). While some members are open to raising banks' reserve requirements (which are non-interest-bearing), we believe this would be a risky move, as it would penalize the weakest banks (which have fewer reserves and liquid assets) and could make the ECB's use of unconventional instruments less effective in the future. Moreover, such a measure is difficult to decide before the conclusion of the review of the ECB's operational framework, which, according to the latest rumours, is not due to take place until 2024.

All in all, the change in rhetoric from central bankers over the past week is in line with our scenario, which does not foresee any further rate hikes between now and the end of the year for the ECB and the Fed, even if for the latter the risk of a final hike (in November and even more so in December) remains significant given the resilience of the US economy. With regard to the reduction of the ECB's excess liquidity, we believe that a majority of members will prefer to bring forward the end of reinvestments in the PEPP rather than raise the reserve requirement rate for banks, which could happen as early as 2024. While our scenario is slightly more favorable for commercial banks, it would also slightly increase the risk for the debt of the Eurozone's riskiest countries, as the PEPP is the tool that gives the ECB flexibility in the geographical distribution of the public bonds it holds.

Fig.3 Markets: Italian spread dips slightly below 200bp

However, Italian spreads (i.e. the difference between Italian and German 10-year yields) are tightening a little this week, after a sharp divergence since September, dropping back to just under 200bp. In our view, this reflects the impact of falling long-term yields, which are taking some pressure off riskier assets, and the fact that the EU has finally released the third tranche of European aid to Italy, which had been pending since March (for a total of €18.5 billion).

However, we remain cautious about Italian debt between now and the end of the year. Admittedly, we expect risk-free rates to remain stable or even fall slightly, which should be rather favorable for Italian debt. But we believe this support will be limited, as rates will remain relatively high. At the same time, the reduction in the ECB's balance sheet will accelerate somewhat, budget negotiations are likely to be difficult, and the disbursement of the remaining tranches of the European stimulus plan may create further tensions (Italy has yet to receive more than 100 billion of the plan's 192 billion).

Fig.4 United States: SMEs are pessimistic but continue to spend

The Fed's more cautious stance is welcome, as the latest data could have led to a further explosion in rates, given that they indicate that US growth and the labor market continue to be quite buoyant. While this justifies high rates and restrictive monetary conditions, a continuation of the recent trend would, in our view, increase the risk of a sharp recession within a few months.

While US SMEs remain fairly clearly pessimistic in September, they continue to forecast hiring and investment at a relatively high rate. This suggests that companies are continuing to spend despite the pressure on profits. This is reassuring, as changes in corporate spending are usually what drive the business cycle, much more so than the level of optimism reported by business leaders (which is heavily impacted by politics). All in all, the SME survey is yet another sign that the US economy is holding up well.

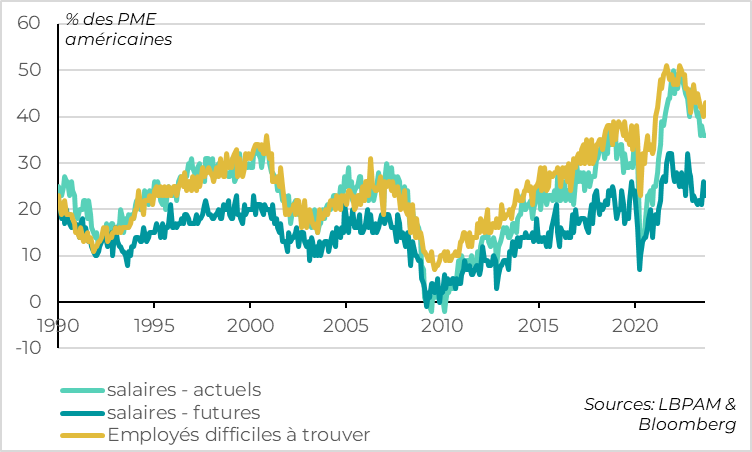

Fig.5 United States: SMEs report that the job market has stopped easing this summer

At the same time, SMEs indicate that the slight re-acceleration of the economy this summer has led to a slowdown in progress on inflationary pressures. This supports our view that, to bring inflation fully back to the 2% target, it is likely that growth and the labor market will have to decline more than the consensus and the Fed anticipate.

We attach little importance to price indicators, which have been rising slightly since the summer, as they mainly reflect changes in oil prices. But we do attach importance to what companies are saying about the job market. SMEs report that recruitment difficulties rose slightly again in September, after 6 months of decline, and that they remain above their pre-crisis level. This is consistent with the rise in job vacancies in August, and suggests that tensions on the labor market persist, even if they are less extreme than in 2021-2022. And these tensions are keeping up the pressure on wages. Indeed, companies report that wage growth has stopped slowing this summer, and that wage prospects remain slightly stronger than before the Covid.

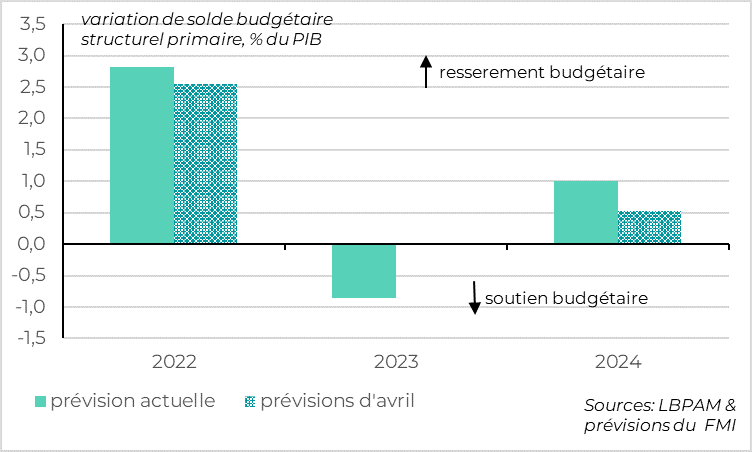

Fig.6 Developed countries: the IMF considers that fiscal support was substantial this year

The IMF has published its semi-annual forecast update, which offers few surprises. Global growth forecasts remain unchanged at a modest level (at 3.0% in 2023 and 2.9% in 2024 after 3.5% in 2022), with stronger US growth offsetting weaker growth in the Eurozone and China.

But, as we expected, the IMF has significantly revised its fiscal support for growth this year, particularly in the US. Thus, the IMF estimates that fiscal policy has been eased by 0.9pt of GDP this year in developed countries, compared with a zero estimate in April. This comes on the back of strong support of almost 2pt of GDP in the US, a rare event at a time when US growth was at a normal level. Fiscal policy was also accommodative in Europe in 2023, according to the IMF, but in a much more measured way (0.25pt of GDP).

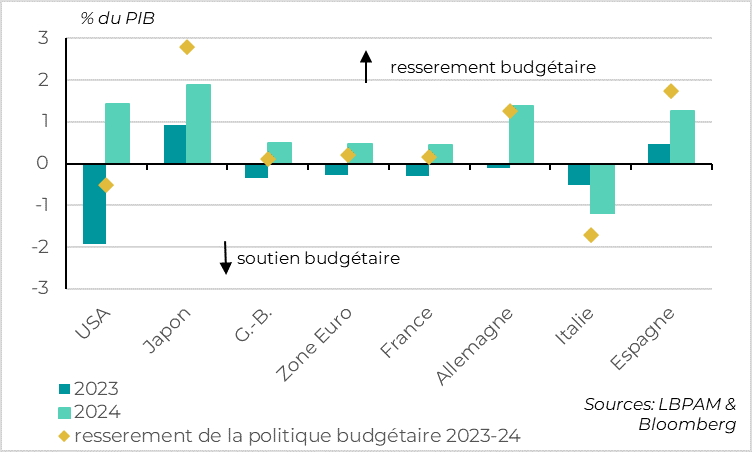

Fig.7 Developed countries: ... especially in the United States, but fiscal policy should be fairly restrictive next year

Against this backdrop, it is less surprising that growth in the US has been more resilient than expected this year, and that interest rates need to be higher for longer to reduce the economy's overheating.

But the IMF predicts a return to fiscal tightening in all developed countries (except Italy). This is one of the reasons why we expect growth to be much more limited than anticipated by the consensus, central banks and the IMF next year on both sides of the Atlantic.