Growth also pushes rates higher

Link

-

The market remains on the defensive this week, still impacted by the Fed's reduced expectations of rate cuts and the risks of escalating tensions between Israel and Iran. As a result, oil remains above $90 a barrel, interest rates are at their highest since November on both sides of the Atlantic, as is the dollar. These conditions are weighing on risky assets, but they are holding up fairly well thanks to the favourable economic outlook (the IMF has revised upwards its global growth forecast by 0.1pt to 3.2% for this year). This is benefiting gold in particular, which is at an all-time high despite the rise in the dollar and real interest rates.

-

US growth is still not slowing down in March and remains above potential in Q1, which is not going to push the Fed to hurry up and start cutting rates. Core retail sales accelerated from 0.3% to 1.1% in March, suggesting that consumption remained buoyant in Q1 and will maintain good momentum at the start of Q2. In addition, manufacturing output rose to its highest level since 2022. Only housing activity disappointed in March, probably impacted by the further rise in lending rates. In these conditions, even Powell is becoming more cautious, indicating that the Fed can remain inactive "for as long as necessary".

-

In Europe, activity remained limited at the start of the year, but the outlook is still improving. Industrial production rebounded slightly in February after a sharp fall in January, and the ZEW survey indicates growing investor confidence in a recovery during 2024.

-

In the UK, if growth picks up again in early 2024, employment will fall even if it does not collapse. This should limit the strength of the recovery in consumption somewhat, but it does ease tensions on the labour market. As a result, the number of job vacancies per unemployed person is finally returning to its pre-Covid level. This easing is necessary to allow a further slowdown in wages, which are still growing twice as fast, and probably the start of a slowdown in inflation in services. If this is the case, it could enable the Bank of England to start cutting rates this summer.

-

Chinese growth accelerated more than expected in Q1, from 5.2% to 5.3% year-on-year. This good start should enable the authorities to achieve the 5% target for this year. That said, growth is very unbalanced. It is being driven by external demand and public investment, while private domestic demand remains weak, particularly but not exclusively in the property sector. In addition, activity slowed somewhat across the board in March and deflationary pressures remain significant.

-

Without greater fiscal stimulus, we expect growth to slow again from the summer onwards after a fairly buoyant first half of the year. This is all the more true given that pressure against Chinese exports is increasing after their sharp rise at the start of the year, from both the Biden administration and the European Commission.

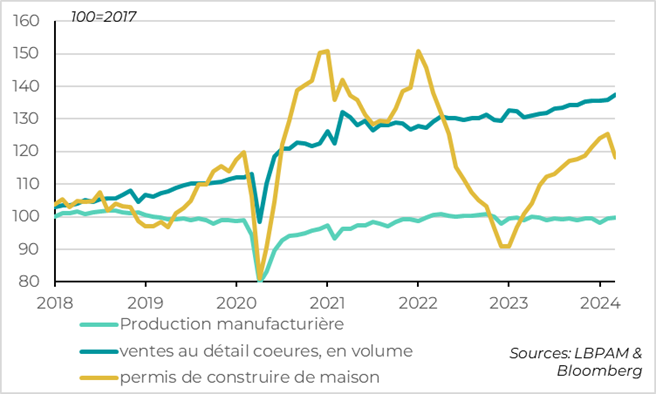

Fig.1 United States: growth remains dynamic in March, apart from construction

- Manufacturing output

- Coeures retail sales, in volume

- Building permits for houses

The data for March show that US growth is still not slowing down in Q1 and remains above its trend rate.

Retail sales rose by 0.7% in value terms in March, following a stronger rise than initially estimated in February (0.9% instead of 0.6%). Above all, core retail sales, which are used to estimate the consumption of goods in GDP, rose by 1.1% in March. Since core goods prices fell slightly in March, this means that goods consumption in volume terms is dynamic at the end of the quarter. US household consumption continues to grow at a rate of over 3% in the first quarter and is maintaining a favourable momentum at the start of Q2, which limits the risk of an abrupt slowdown in growth in the middle of the year.

Furthermore, US industrial production rose by 0.4% in March for the second month in a row. It was driven by industrial production, which reached its highest level since 2022 after stabilising at the start of the year.

Only housing activity disappointed in March, with a sharp fall in housing starts and building permits more than reversing its February rebound. This suggests that the rise in mortgage rates, which rose above 7% in April, is once again weighing on activity. That said, building permits for single-family homes, the least volatile series, fell for the first time in 15 months in March, but remained up slightly over the quarter. This suggests that residential investment will remain positive in Q1, as it has been since mid-2023, even though the outlook for the sector has darkened slightly.

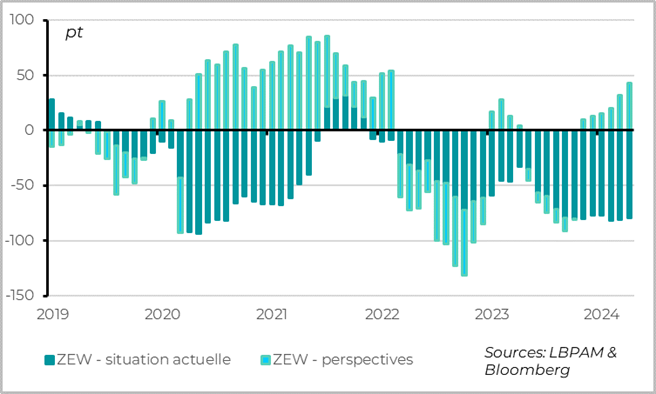

Fig.2 Germany: the outlook continues to improve in April

- ZEW - current situation

- ZEW - outlook

In the Eurozone, signs of a gradual recovery are accumulating, even if activity remained limited in Q1.

Industrial production recovered slightly in February after its sharp fall in January (+0.8% after -3.0%). It remains lower than at the end of 2023, but is regaining some momentum.

The ZEW investor survey also continues to point to a future recovery. The indicator for current activity in Germany remains very weak in April, although it is up slightly on Q1. Above all, the business expectations indicator continues to move even further into positive territory, at its highest level since the start of the invasion of Ukraine.

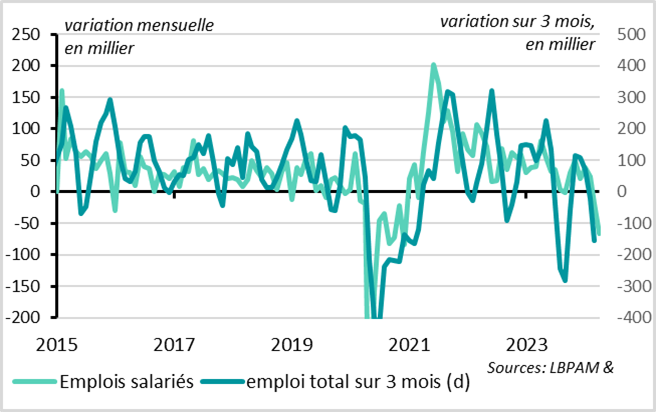

Fig.3 United Kingdom: employment falls in early 2024

- Salaried jobs

- Total employment over 3 months (d)

Although UK activity picks up at the start of 2024 (GDP up by 0.1% in February after +0.3% in January), employment falls by 156 thousand between November and February, which is the sharpest fall since mid-2023.

This fall is probably exaggerated, given the high volatility of the British employment measure in the short term, but it is corroborated by a fall in salaried employment reported by companies. In fact, salaried employment has fallen over the last two months for the first time since 2020 (-66 thousand in March after -18 thousand in February). This is consistent with the contraction in activity in the second half of 2023, as employment is a lagging indicator of the cycle. This is a brake on the prospects for a recovery in consumption, which should nonetheless benefit from the improvement in real household incomes and the already high savings rate.

That said, this deterioration in employment does not suggest a collapse in the labour market, especially given the improved economic situation. The number of job vacancies remains on a downward trajectory, but stabilised in March after almost two years of uninterrupted decline (+6 thousand). Claims for unemployment benefit rose slightly, by 10,000 in March, but this remains a limited level.

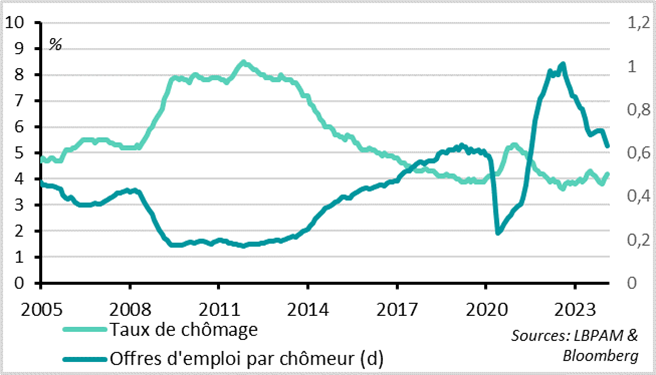

Fig.4 United Kingdom: tensions on the labour market ease

- Unemployment rate

- Job vacancies per unemployed person (d)

This slowdown in employment means that tensions on the labour market are easing, finally returning to close to their pre-Covid level. This is positive for the Bank of England, as it suggests that price and wage pressures will continue to normalise.

The unemployment rate rose from 4.0% to 4.2% in February, returning to its mid-2023 level. It is therefore back slightly above its level just before Covid.

Furthermore, the rise in the number of unemployed, combined with the downward trend in job vacancies, means that the job vacancy rate per unemployed person returned to its pre-Covid level in February (at 0.63). This is important because this ratio is a leading indicator of wage pressures, and is less volatile than the unemployment rate.

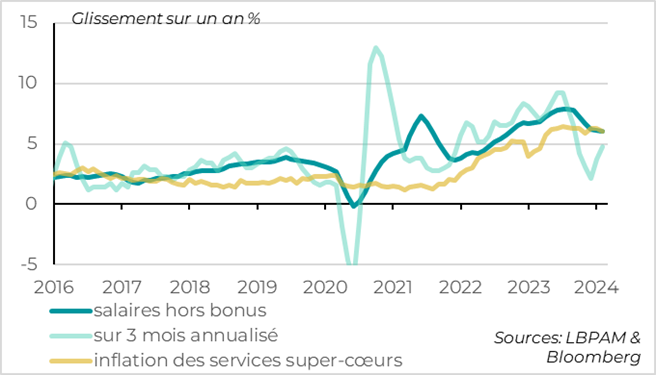

Fig.5 United Kingdom: wages slow, but slowly

- salaries excluding bonuses

- over 3 months annualised

- inflation in super-core services

Wages are slowing even though they are still too high, which gives reason to hope that the price of domestic services is starting to slow, albeit slowly. Weekly wages excluding bonuses slowed from 6.1% to 6.0% year-on-year in February. This is their lowest level for a year and a half, although it is still twice as high as before Covid. On a sequential basis, wages are picking up slightly after a sharp slowdown at the end of 2023, although they remain consistent with a further slowdown towards 5%.

For the time being, the deterioration in the labour market and the slowdown in wages are a little slower than the Bank of England expected in February, when the recovery was a little faster. This could lead it to wait before starting to cut rates. However, disinflation is expected to make more headway in Q2, which could push the BoE to start cutting rates in August, at least if the Fed does cut rates in July.

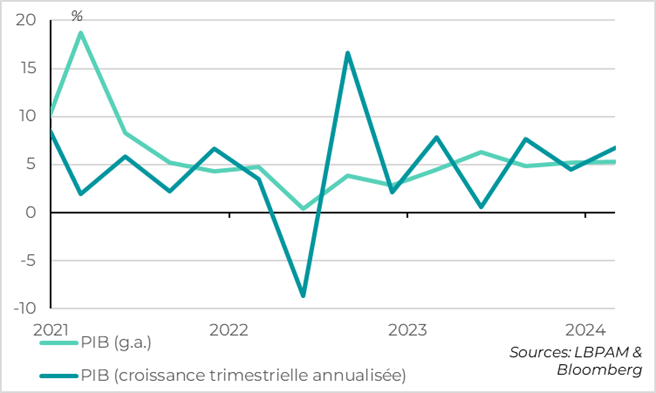

Fig.6 China: Chinese growth accelerates slightly at the start of 2024, above the authorities' target

- GDP (g.a.)

- GDP (annualised quarterly growth)

China's GDP growth accelerated from 5.2% to 5.3% year-on-year in the first quarter according to the authorities, while expectations were for a slight deceleration due to unfavourable downside effects (i.e. recovery after the end of the Zero-Covid policy at the beginning of 2023). Over the quarter, growth accelerated from 1.2% to 1.6%, or almost 6.5% on an annualised basis.

This confirms that activity was solid at the start of 2024, and makes the authorities' 5% growth target for this year achievable even if growth slows in the coming quarters.

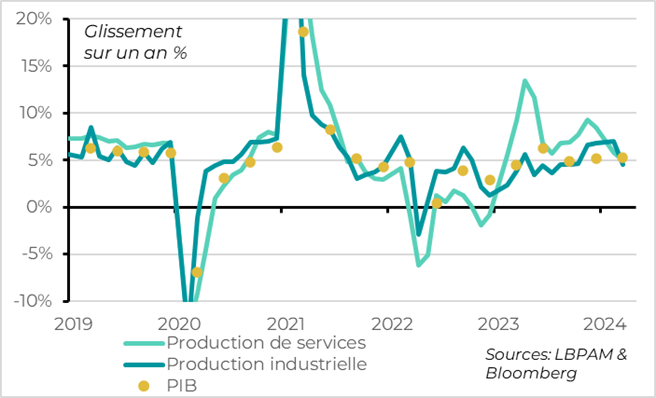

Fig.7 China: but growth remains unbalanced and slows at the end of the quarter

- Service production

- Industrial production

- GDP

That said, the outlook remains less encouraging, and we continue to expect a further deceleration in activity in the second half of the year if the authorities do not offer more fiscal support.

Growth in Q1 was very unbalanced, driven by external demand and public demand, while private domestic demand remained weak, especially, but not only, in real estate.

On the production side, growth is being driven by the industrial sector (production up by 6.1% in Q1 after 4.6% in 2023), while the production of services, which had driven the recovery at the start of 2023, is slowing (5.5% after 8.1%). On the demand side, growth is being driven slightly by external demand and above all by public sector investment (+7.8% in Q1), while private investment remains sluggish (+0.5%) and retail sales remain limited (+3.1%).

In addition, growth lost a little momentum in March, although the annual figures exaggerate this slowdown due to unfavourable base effects. Growth benefited above all from strong activity in January-February, but slowed slightly in March. While the slowdown in retail sales from 5.5% to 3.1% is mainly due to base effects and the volatility of car sales, the slowdown in industrial production from 7% to 4.5% is more worrying.

Finally, the structural brakes on growth persist, as the property sector still does not seem to be stabilising and deflationary pressures remain significant. Construction investment fell by a further 9.5% in Q1, at the same rate as in 2023. Sales and housing starts continue to contract sharply, and house prices are still falling. On the price side, the GDP deflator was negative for the fourth consecutive quarter in Q1, for the first time in over 20 years, at -1.1%. This reflects the weakness of domestic demand and overcapacity, weighing on corporate profits and reinforcing the problems of over-indebtedness in highly indebted sectors.