Job markets slowing, even in the US

Link

-

The combination of less aggressive rhetoric from central banks at their latest meetings and weaker economic data contributed to a sharp fall in long yields and a rebound in equities. For example, the US 10-year yield fell back below 4.6% for the first time in a month, after touching 5% two weeks ago. This has helped to ease yields in Europe, with French yields below 3.25% for the first time since September. And this easing in long yields is supporting a slight rebound in equities, which are up 5% over the past week. This is in line with our scenario, but we believe that the adjustment has been rapid and that the fall in rates and the rebound in equities could be slower from now on.

-

Labor market reports in the US, Canada and, to a lesser extent, the Eurozone were weaker, and business surveys were disappointing in October. This reinforces the belief that the major central banks are done with rate hikes. And while we shouldn't overreact to some of the data, it does support our scenario of a fairly marked slowdown in US growth over the next few months. Combined with a further slowdown in underlying inflation in early 2024, we believe that central banks could even start considering gradual rate cuts in the first half of 2024, sooner than they and the market currently anticipate.

-

Payroll job creation in the USA halved in October, to 150,000, and was revised sharply downwards. In addition, the unemployment rate rose again to 3.9%. This is still below the equilibrium level estimated by the Fed (4.0%), but higher than the 3.8% rate anticipated by its members in September for the end of the year. The easing in the job market is allowing wages to slow from 4.4% to 4.1%. All in all, this is good news for the Fed in its quest to reduce inflation, but bad news for consumers and the economic cycle.

-

For the Eurozone, the September unemployment rate rose from 6.4% to 6.5%. In fact, the unemployment rate has stopped falling since the spring and should start to rise again slightly at the end of 2024. That said, employment is holding up well compared with activity, which is stagnating. And we believe that the weakening of the labor market will remain limited, allowing household purchasing power to rise thanks to lower inflation, and thus enabling the economy to avoid a sharp recession. That said, the latest figures suggest that the risk of a further slowdown in the job market cannot be ruled out.

-

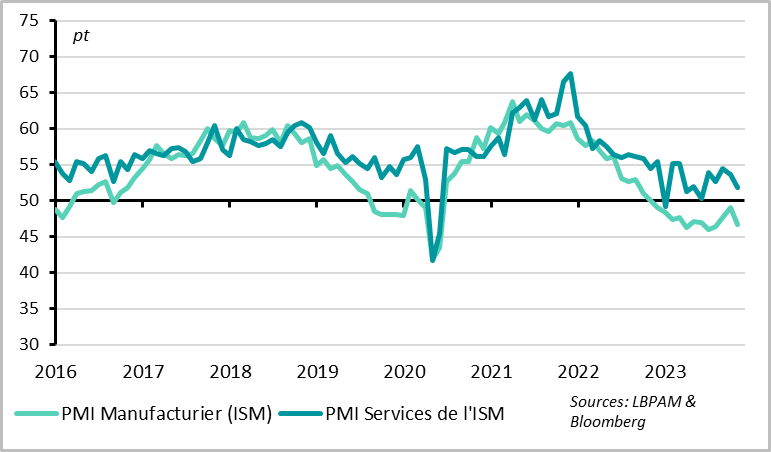

Weakening labor markets go hand in hand with disappointing business surveys. Indeed, the ISM services index, the most important survey for the US economy, fell quite sharply in October, from 53.6 to 51.6pt. Unlike the European PMIs, the ISM remains above 50 points, but its sharp fall in October suggests that the rebound in US growth this summer is well behind us.

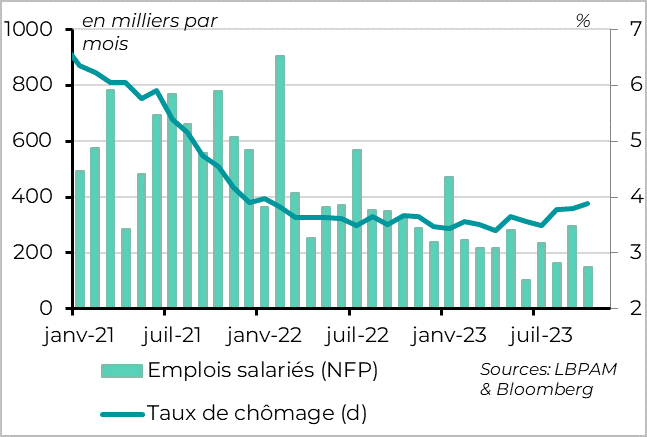

Fig.1 United States: Job market slows sharply in October

-Salaried jobs (NFP)

-Salaried jobs (NFP)

-Unemployment rate (d)

Job creation slowed sharply in October. At 150,000, job creation slowed by half compared with September's very high level. This remains a fairly high level (the Fed estimates that trend job creation should be around 100 thousand at equilibrium) but, unlike the previous month, indicates a continuation of the gradual slowdown in the job market. In particular, the number of jobs created over the previous two months has been revised downwards by 100 thousand.

The auto strikes, which are now over, explain part of the weakness in October (~50,000 fewer jobs). But they do not explain the entire slowdown, nor the sharp downward revisions for the previous months.

Above all, the details of job creation are not very reassuring. Job creation remains strong in the public sector, but the private sector is creating just 99,000 jobs, compared with 226,000 in September. And within the private sector, job creation is concentrated in the health care and social assistance sector (77 thousand), where wages and productivity are low, while employment is falling in industry and high value-added services.

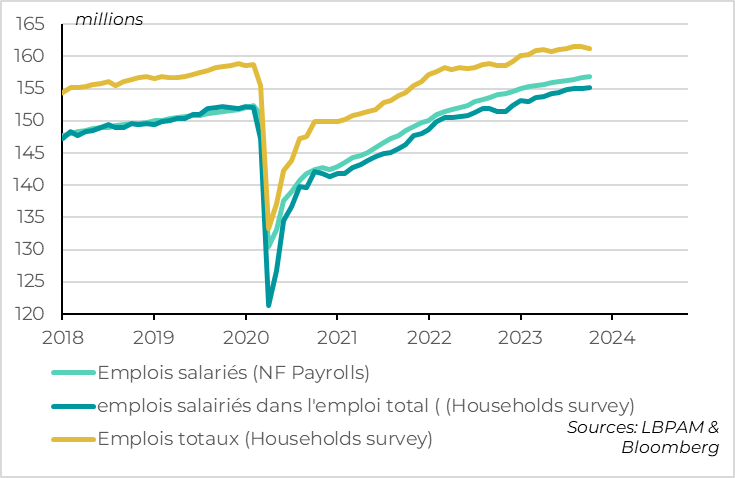

-Salaried jobs (NF Paryrolls)

-Salaried jobs as a percentage of total employment (Households survey)

-Total employment (Households survey)

The household survey is even weaker. However, this survey is more volatile, and has the great advantage of not being revised (and revisions to payroll employment are usually massive when the cycle turns).

Total employment fell by 348 thousand in October, following a rise of just 86 thousand in September. This is the biggest drop since the Covid.

The difference between the business survey and the household survey is partly due to the lower number of salaried jobs created in the household survey (100 thousand versus 200 thousand per month over the last three months), but also to differences in definition between the two surveys. Indeed, the increase in the number of employees holding several jobs, workers returning from unpaid leave and the higher number of self-employed becoming salaried employees are not taken into account in the business survey. All in all, this suggests that salaried employment should be revised downwards a little, but not massively.

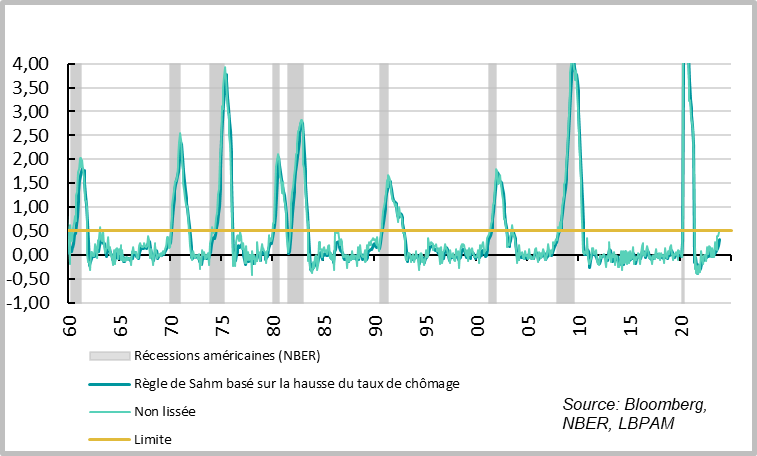

Fig.3 United States: rising unemployment rate suggests significant risk of recession

-US recessions (NBER)

-Sahm rule based on rising unemployment rate

-Unsmoothed

-Limit

Finally, the unemployment rate based on the household survey rose from 3.8% to 3.9% in October, its highest level since early 2022. It remains below the equilibrium rate estimated by the Fed (4.0%) but is above the Fed members' forecasts for the end of 2023 (3.8%). This should prompt the Fed to be cautious.

In terms of the business cycle, Sahm's rule of thumb states that when the 3-month average unemployment rate is 0.5 points higher than its low point of the previous year, the US is in recession. We're not there yet (we're at +0.3pt in October), but we're getting close (the unsmoothed 3-month unemployment rate is up 0.5 points on its April low). This supports our scenario, which forecasts a marked slowdown in US growth over the coming quarters, with the risk of a mild recession in early 2024.

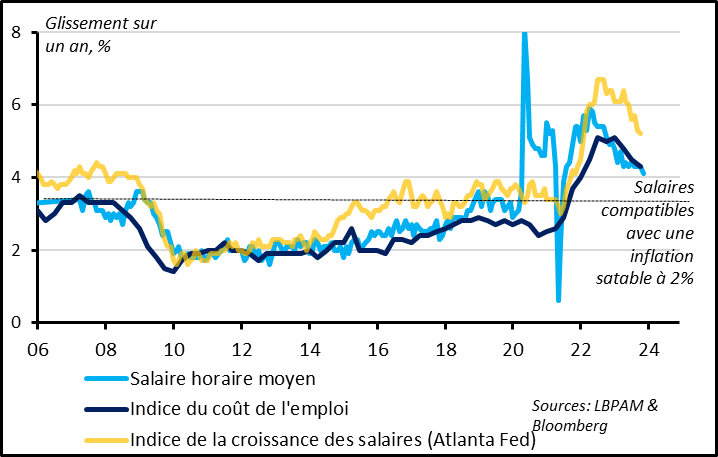

Fig.4 United States: Slowdown in wages should reassure the Fed

-Average hourly wage

-Employment cost index

-Wage growth index (Atlanta Fed)

The good news for the Fed, but not for consumption, is the slowdown in wages. The slowdown in the job market is allowing wage growth to slow, with average hourly earnings slowing from 4.3% to 4.1% in October. Although wages remain above the level compatible with inflation lasting at 2%, this is their slowest rate of increase since mid-2021. This should reassure the Fed after wage costs surprised on the upside in Q3 (to 4.6%). On the other hand, the slowdown in employment and the decline in hours worked do not bode well for household incomes.

Fig.5 United States: Financial conditions have eased according to the Fed, but remain more restrictive since the start of 2023

-Manufacturing PMI (ISM)

-ISM PMI Services

Beyond employment, business surveys also suggest a slowdown in US momentum in October. The ISM services index fell for the second month running, from 53.6 to 51.8pt, returning to its pre-summer growth rebound level. It remains in the expansion zone, but suggests that growth will fall back below potential at the start of Q4. This weakening is also visible in the ISM manufacturing index, which fell sharply in October after stabilizing in previous months.

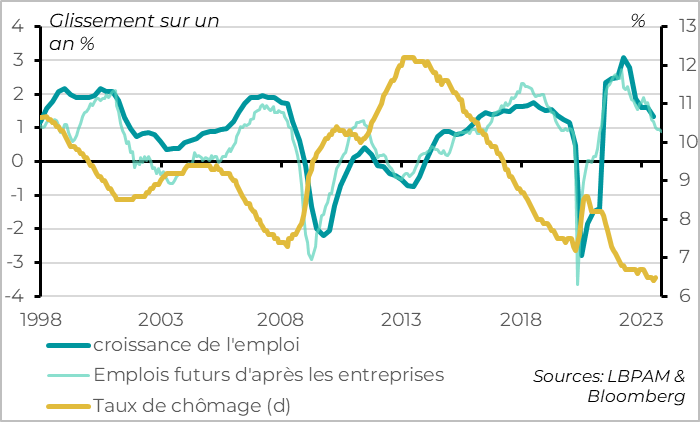

Fig.6 Eurozone: job market also slows down, without collapsing

-Employment growth

-Future jobs according to companies

-Unemployment rate (d)

For the Eurozone, the unemployment rate rose slightly in September, from 6.4% to 6.5%. But beyond the volatility of the month, the unemployment rate has been stable overall since the 2nd quarter, at 6.4-6.5%, which remains its lowest level since the creation of the Eurozone.

The number of unemployed has not fallen since June, and even rose slightly this summer, reaching 11 million in September. This reflects the slowdown in employment growth, which probably fell below 1% this summer after its strong post-Covid rebound. However, employment still seems to be holding up well as activity stagnates year-on-year (+0.1% in Q3).

We expect employment to remain resilient despite the absence of growth over the next few quarters, with stagnation or even a marginal decline in employment over the coming months. Indeed, the number of job vacancies remains abnormally high, and companies are indicating that recruitment difficulties remain very high. If this is the case, household purchasing power should remain positive, thanks to inflation falling faster than wages. This explains why we do not anticipate a real recession in the Eurozone in the coming quarters. However, the sharp drop in employment components in the October PMIs and national surveys suggests that the risk of a more marked decline in employment remains present.