Questions raised over the decline in US consumer confidence

Link

- The markets got the week off to a mixed start, torn between hopes of progress in negotiations on raising the US debt ceiling and fears of recession and stubborn inflation.

- President Biden reported progress in negotiations aiming to head off a payment default and said that he would meet leading members of Congress tomorrow, the second meeting in one week. This is good news, given that the debt ceiling could be constraining as soon as early June, according to the US Treasury and given that market tensions are still at an all-time high (with the one-year sovereign CDS at 177bp).

- Meanwhile, US consumer confidence fell more than expected in early May, to a low since the end of last year. This is not encouraging, given that growth in the US has been driven solely by consumer spending so far this year. While household income is holding up well, it is still being undermined by a further increase in inflation expectations. The Fed is likely to take a dim view of the increase in long-term household inflation expectations to a 15-year high. This exacerbates the risk that the Fed will have to raise its rates further, although our scenario is still for a long plateau of rates at their current level of 5.1%. As the markets are still pricing in three rate cuts by the start of 2024, the markets would appear to offer little upside.

- Like the Eurozone, the United Kingdom avoided a recession this winter. GDP rose by 0.1% in Q1, as in Q4[A1]. That said, UK GDP fell by 0.3% in March, suggesting that growth should remain weak in Q2. Moreover, three years after the start of the pandemic UK GDP is merely at its pre-Covid level, while it is 5.3% higher in the US and 2.5% higher in the Eurozone.

- The Bank of England has raised its growth outlook aggressively and, for the first time in one year, it is no longer forecasting a recession for 2023-2024. However, it does forecast weak growth (0.3% and 0.8%) and, more to the point, more stubborn inflation, due in particular to still heavy tensions on the job market. Accordingly, it doesn’t see inflation hitting its 2% target until 2025, vs. mid-2024 in its February projections. All in all, while we believe the Bank of England is close to a peak in its rate-hike cycle now that its policy rate is 4.5%, one last rate hike in June is possible – especially if the jobs reports due out tomorrow suggest that wages once again failed to slow in March.

The outcome of Turkish presidential elections appears to be pointing towards a second round of voting in two weeks, with the incumbent president, Erdogan, scoring 49.5%, based on the latest polls (vs. a little less than 45% for his opponent Kemal Kilicdaroglu). That said, the outcome is rather encouraging for Erdogan, whose party is expected to hold onto its majority in parliament and who has a big chance to win the second round. This reduces short-term uncertainties on Turkey but heightens medium-term geopolitical risks (Turkey being a NATO member). Geopolitical issues are likely to remain in the forefront this week with the meeting of G7 heads of state in Japan on Thursday and Friday. Talks are expected to centre on new assistance to Ukraine, a strategy to diversify production chains (mainly with regards to China) and strengthened financial regulations.

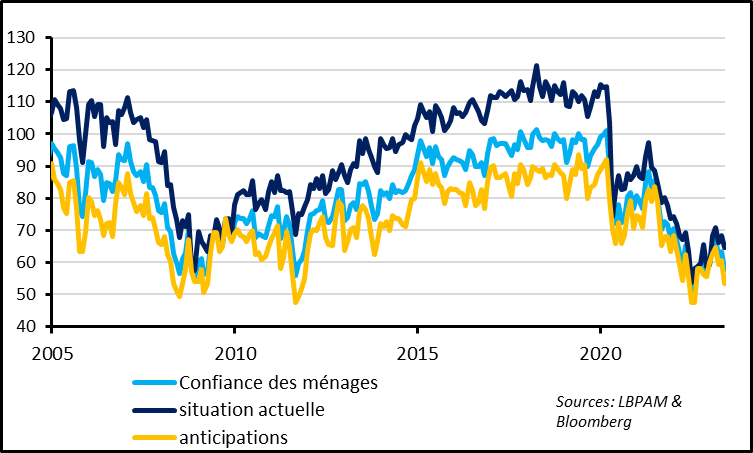

Fig. 1 – United States : consumer confidence down sharply in early May

According to the University of Michigan survey, US consumer confidence fell from 63.5 to 57.7pt in early May, a low since the end of last year. We would caution against overreacting to a decline in this indicator, which can be volatile from month to month and has historically been driven by political considerations, which ultimately have no impact on the economy. Even so, the decline in consumer confidence in May is due in part to the (modest) decrease of the household current situation component, which is historically a bellwether of the US economy. Moreover, consumer confidence is currently more important than usual, given that US growth has been driven solely by consumer spending so far this year. A weakening in this GDP component would exacerbate the risks of a marked slowdown in the US economy in the coming months, as we expect.

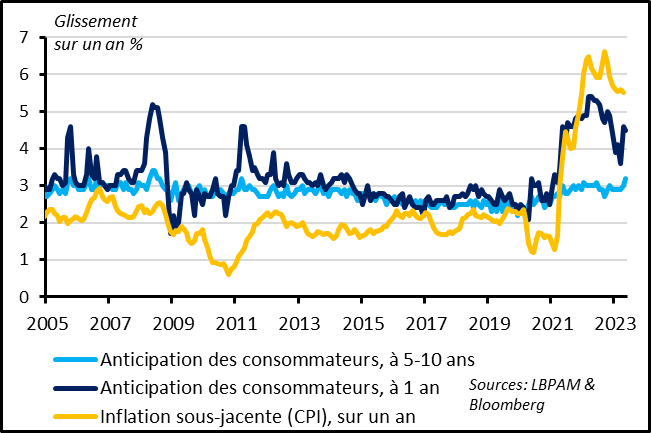

Fig. 2 – United States : household inflation expectations up once again, which is not a good sign for the Fed

The decrease in consumer confidence in May is due mainly to the increase in inflation expectations, which are weighing on the purchasing power outlook despite the resilience in expected income. Household inflation expectations one year out remain high after rebounding in April, to 4.5%. This is rather surprising, given that gasoline prices have settled back after rebounding in April. Most importantly, long-term expectations (5-10 years) rose sharply in early May, from 3% to 3.2%. This is higher than in 2022 and a high since 2008.

If this increase in long-term household inflation expectations is confirmed in the coming surveys, that would step up pressure on the Fed. Indeed, an upward de-anchoring of inflation expectations would make it more different to get inflation back to the 2% target, which, in turn, would require more restrictive monetary policy to provide convincing evidence that the Fed is willing to do whatever it takes to lower inflation to its target rate, even if that carries an economic cost.

Until now, long-term inflation expectations of both households and the markets have remained well-anchored in this inflation cycle, which supported our view that the Fed is likely to be able to lower inflation to its target by sticking to a policy as restrictive as it is currently for several more quarters. But if inflation expectations do rise, the Fed would have to raise its rates higher. This underpins the idea that interest-rate risk remains on the upside, although the central scenario is that the Fed has probably completed its rate hikes.

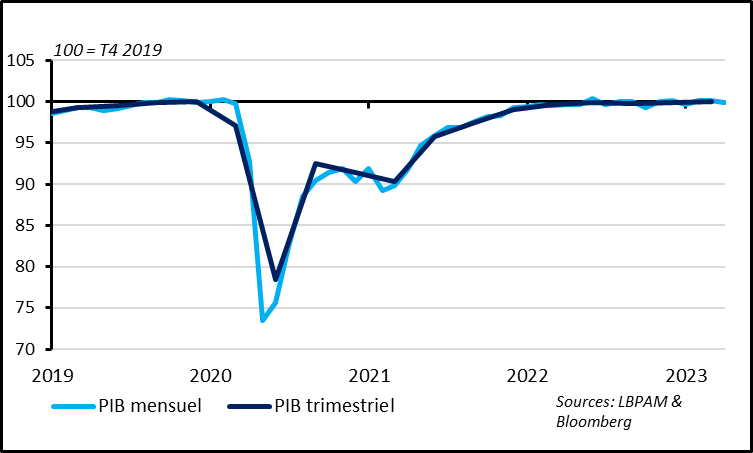

Fig. 3 – United Kingdom : GDP up slightly in Q1 but down again in March

UK GDP rose by 0.1% in Q1, in line with forecasts and as in Q4 2022. This confirms that, like the Eurozone, the UK managed to avoid a recession this winter, despite weak growth. Moreover, the Bank of England last week raised its GDP forecasts and is no longer forecasting a recession for 2023 and 2024.

Broken down by components, private consumption stagnated, while public consumption is beginning to adjust downward. The good news was the rebound in business investment (+0.7%), although it remains below its pre-Covid level.

Month-on-month, GDP shrank by 0.3% in March after stagnating in February, ending the quarter at 0.1% under its Q1 average. That means that Q1 growth was driven solely by the rebound of GDP in January and suggests that growth is likely to remain low in Q2.

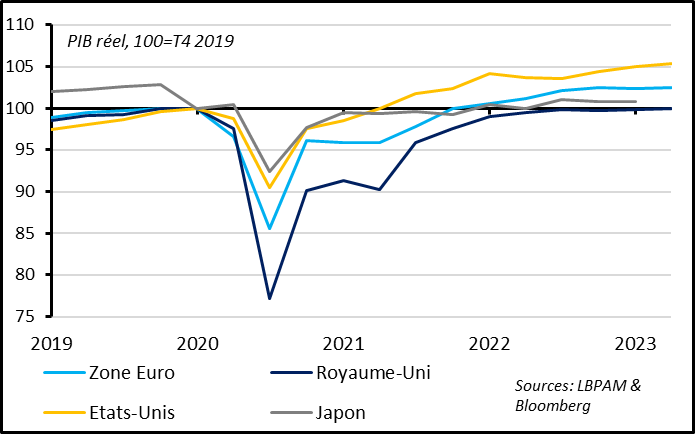

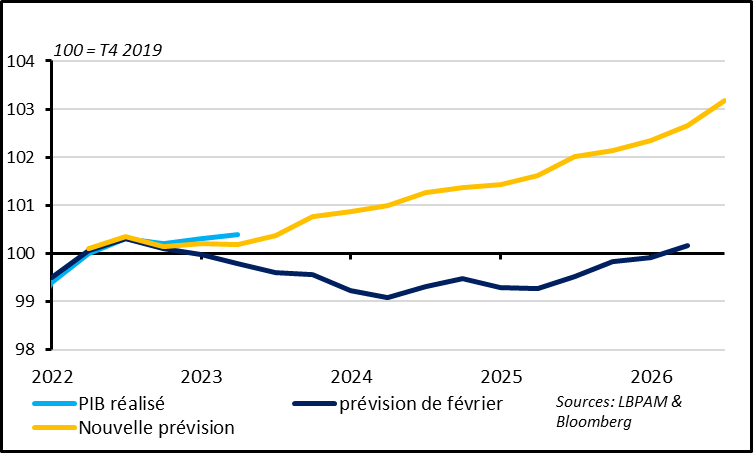

Fig. 4 – United Kingdom : GDP stagnating at its pre-Covid level, underperforming other major developed countries

UK economic activity has been almost stagnant since mid-2022 and has merely returned to its pre-Covid level. This is not as good as the Eurozone (+2.5%) and the US (+5.3%) and is the worst performance of G7 countries (along with Germany).

Fig. 5 – United Kingdom : for the first time in a year, the Bank of England is no longer forecasting a recession for 2023-2024

The Bank of England (BoE) raised its growth forecasts sharply in May but still projects weak growth for 2023 and 2024, at 0.3% and 0.8%, respectively[A1] , whereas in February it had been projecting a two-year decline in GDP. This is the BoE’s biggest upward revision in growth since it has been reporting its forecasts and the first time in a year that the BoE has not forecast a recession. The BoE explained these new forecasts by the economy’s better resilience this winter, in particular the job market, the steep decline in energy prices, and by fiscal policy that is less restrictive than expected. Keep in mind, however, that the BoE’s growth forecasts remain low, and below trend out to 2025.

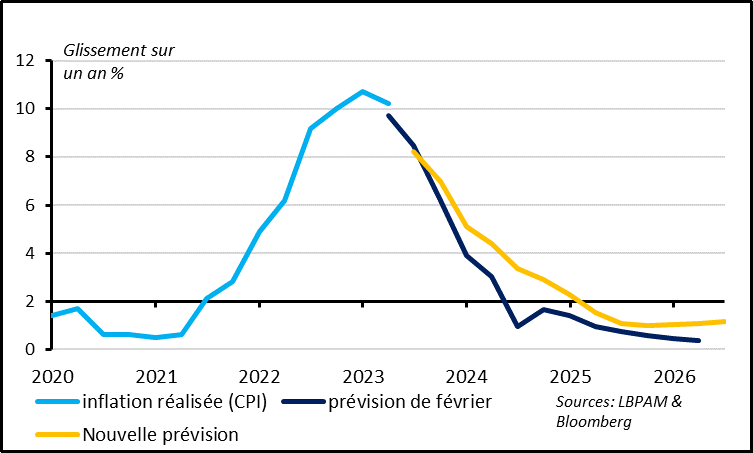

Fig. 6 – United Kingdom : but the Bank of England forecasts a slower receding of inflation, which would not hit 2% until 2025

Alongside its growth revisions, the BoE has raised its inflation forecasts markedly, as inflation remains higher than expected (at more than 10% in March), with wage growth still not slowing and with the economic outlook not as bad as expected. Most importantly, the BoE doesn’t expect inflation to hit its 2% until 2025, vs. mid-2024 in its February forecasts and doesn’t expect inflation to move significantly below its target in the coming years. This points to a longer-lasting restrictive monetary policy.

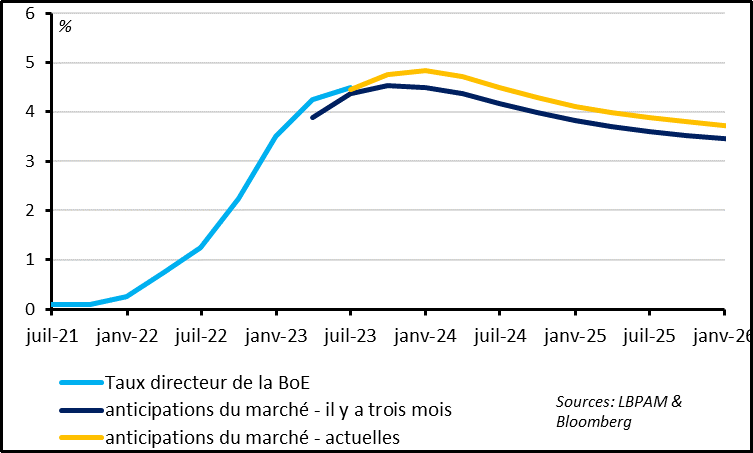

Fig. 7 – United Kingdom : the Bank of England is close to the end of its rate-hike cycle but one last increase in June is possible

Since March, the BoE had flagged that it was near the end of its monetary tightening cycle. However, it once again raised its rates last week, to 4.5%. While we believe the BoE could stick to these rates in the coming quarters, the risk of an additional rate hike in June, as the markets are pricing in, is clearly significant. Keep an eye on this week’s jobs reports to see whether the economy and wage pressures remain more resilient than expected.