Latest data give ECB little room for manoeuvre

Link

- Interest rates have eased slightly since the start of the week, after US 10-year yields rose above 5% during Monday's session for the first time since 2007. That said, long rates remain very high, while the economy is showing signs of weakness outside the US, particularly in Europe. The slight easing of rates and the absence of further bad news from the Middle East are stabilizing risky assets, but macro and micro uncertainties are limiting the potential for a rebound.

- The Eurozone PMI resumed its decline in October, pointing to a further contraction in GDP at the start of Q4.At the same time, consumer confidence remained weak in October after two sharp declines in the summer, although it remains above the levels of previous recessions.We continue to believe that activity in the Eurozone will stagnate for several quarters, but the latest data indicate a significant risk of recession.

- The Eurozone bank lending survey shows that the supply of credit continues to tighten sharply in the second half of the year and, above all, that demand for business and property loans has contracted sharply since the start of the year.And this dynamic, which can be explained by the monetary tightening that has already taken place over the past year and a half, is set to continue until the end of the year.

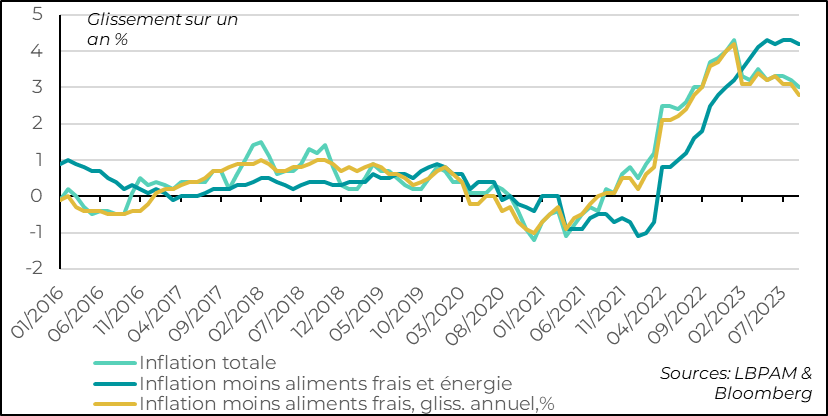

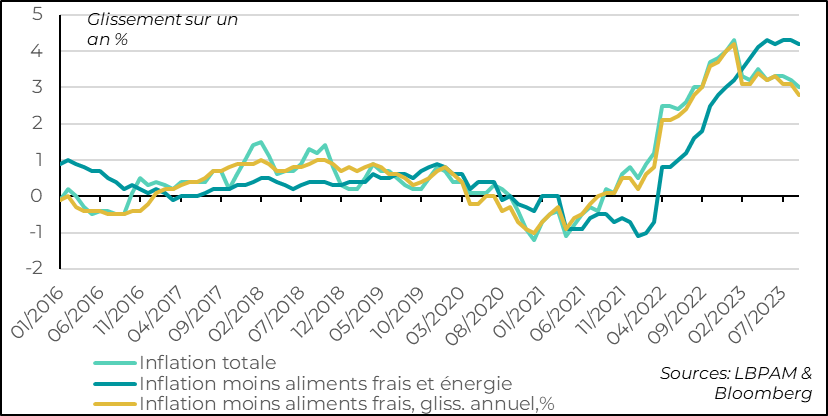

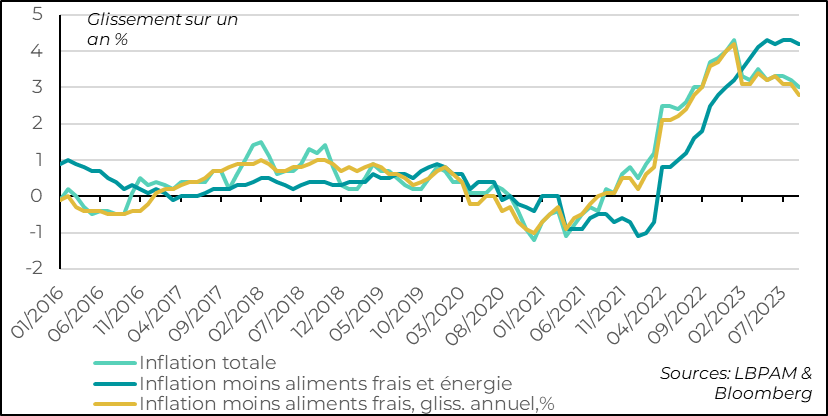

- All in all, the latest data should prompt the ECB to adopt a cautious stance.On the one hand, inflation trends remain in line with the ECB's September forecasts, which do not call for a return to 2% until the very end of 2025. This should prevent the ECB from getting comfortable on inflation. On the other hand, growth momentum is weaker than the ECB anticipated in September, financial conditions are tougher and the transmission of monetary policy is clearly visible via the banks. In this context, we believe that the ECB should leave its key rates unchanged after 10 consecutive hikes (the deposit rate at 4%), without saying that it is finished with rate hikes, and should insist on the need to keep rates high for a long time. With rates on a plateau, the debate is likely to turn to reducing liquidity (via the sale of held bonds, the end of reinvestments in PEPP or raising the reserve requirement ratio for banks). We believe that it is too early and that there are too many uncertainties for the ECB to make precise announcements on this subject this week. But it could give itself some room for manoeuvre by withdrawing its commitment not to reduce outstanding debt in the PEPP before the end of 2024.

- Outside the Eurozone, the PMIs were fairly disappointing, with the exception of the United States, which continued to surprise on the upside. The UK PMI stagnated in contraction territory (48.6pt) for the third consecutive month, while the Japanese PMI dipped below the 50-point mark for the first time since 2022.On the contrary, S&P Global's US PMI, which had been weaker than other economic indicators this summer, rebounded to 51 points after remaining close to the stagnation zone at 50.2pt for two months.

Fig.1 Eurozone: PMI falls to lowest level since 2020 in October

The Eurozone's composite PMI fell again in October, after rebounding slightly in September. At 46.5pt, it is at its lowest since 2020 and consistent with a 0.3% quarterly decline in GDP.

The details of the survey suggest that inflationary pressures are continuing to ease, but at the cost of a sharp drop in business confidence and a deterioration in margins. Companies are becoming more cautious in the face of weak demand. Indeed, S&P reports that eurozone companies are cutting back on headcount in October for the first time since early 2021, and are focusing on managing inventories to keep costs down. On the positive side, price indicators are falling to a two-year low for both goods and services, although price rises for services remain historically very high.

In sectoral terms, the PMI decline is widespread. The manufacturing PMI is approaching its early summer low of just 43pt. Meanwhile, the services PMI continues to fall further into contraction at 47.8pt, a level not seen since the end of containment periods in early 2021.

This is disappointing at a time when Asian data are pointing to the beginning of a stabilization in the global industrial cycle, and lower inflation is expected to support consumer demand.

In geographical terms, the French PMI recovers slightly from its September low, but remains below the Eurozone PMI at 45.3pt. The German PMI cancels out its September rebound, as the services sector returns to contraction territory, while the manufacturing PMI barely stabilizes at just 40.7pt. But the bad surprise comes mainly from the rest of the Eurozone, where the PMI falls sharply into contraction for the first time since 2022. This suggests that the resilience of the Italian and Spanish economies will be put to the test at the end of 2023.

Fig.3 Euro zone: household confidence slightly more resilient than business confidence

Consumer confidence stabilized somewhat in October, but after two sharp falls this summer, it is now at a fairly limited level (-17.8pt). That said, it remains well above its levels of 2022, at the heart of the energy shock, and above its level during previous recessions (-20pt). The resilience of consumer confidence remains in line with our scenario of stagnant GDP thanks to consumption. Indeed, we believe that households are benefiting from lower inflation, a resilient labor market and an already high savings rate. But weak business confidence suggests an increase in recession risks in the second half of this year.

Fig.4 Euro zone: bank lending conditions continue to tighten sharply

The ECB's survey of banks confirms the significant negative impact of monetary tightening on the dynamics of credit and hence activity.

Banks' supply of credit to households and businesses is still falling sharply, even though the pace of tightening has been gradually easing since the start of the year.

But the weakness in credit is mainly due to the sharp fall in demand for credit, particularly from businesses. For the past three quarters, the decline in credit demand from both SMEs and large corporations has been as steep as it was during the financial and debt crises in the Eurozone. And unlike in previous quarters, banks are hoping for only a gradual slowdown in the decline in demand. Household demand for credit is also continuing to fall sharply, albeit slightly less sharply than at the end of 2022-beginning of 2023.

Fig.5 Eurozone: In addition to economic and credit risks, banks are seeing higher costs and lower liquidity.

Banks report that the main reason for the fall in supply is the worsening of macro-economic risks and customers' credit risk outlook. But the rising cost of deposits and declining liquidity also play a non-negligible role. We believe this should prompt the ECB to be cautious about reducing its balance sheet and interbank liquidity. On the credit demand side, companies report that the weakness is mainly due to higher interest rates and lower capital spending. This reflects the expected impact of a restrictive monetary policy, but is not a good sign for the business cycle.

Fig.6 Eurozone: credit conditions are very restrictive and are likely to remain so in 2024

Monetary data already point to a very negative impact of monetary policy on the economy.

Total money supply (M3) fell by 1.3% year-on-year in August, a sharper decline than after the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. The most liquid money supply (M1), which is directly available to support spending in the real economy, even contracted by 10.4% year-on-year. As a proportion of GDP, they have fallen back below their pre-Covid trend.

Growth in loans to businesses and households slowed sharply, to 0.6% and 1% year-on-year in August, and has even fallen slightly since the second quarter. As a result, the contribution of credit growth to economic growth fell to -4.6pt of GDP in August, a more negative level than during the Eurozone debt crisis of the early 2010s. And bank credit conditions suggest that credit momentum will remain very negative until at least mid-2024.

This supports our forecast of still very weak growth in the first part of next year, contrary to the consensus and ECB scenarios, which anticipate a rapid re-acceleration in growth from early 2024. This also implies that the ECB's monetary policy is already very restrictive, hence our forecast that the key rate will no longer rise. In our view, it could even start to fall before mid-2024.

Fig.7 Developed countries: October PMI

Outside the Eurozone, PMIs suggest that global growth is weak outside the USA.

The UK PMI has stagnated in the contraction zone (48.6pt) for the past three months. This is consistent with signs of a slowdown in the job market and business confidence since the summer. The good news is that wages and services inflation are beginning to ease, even if they remain far too high.

Outside Europe, Japan's PMI falls below 50pt for the first time since 2022 due to the slowdown in services, suggesting that support from the lagged reopening of the Japanese economy is fading.

The exception remains the United States, whose S&P Global PMI rebounded to 51 points after remaining close to the stagnation zone at 50.2pt for two months. This reflects an improvement in activity in both services and manufacturing in October, with the manufacturing PMI returning to 50pt for the first time in 6 months. The S&P Global and regional Fed indicators converged in October to point to limited but still positive growth at the start of Q4 in the US.