Risks and opportunities with the return of a true credit cycle in Europe

Link

- The markets are in a wait-and-see mode ahead of the central banks' meetings in the coming days (Fed, ECB, BoE...), while still seeing the glass as half full. Rates have stabilized since last week, but optimism remains high in view of the European and US equity markets, which are at their highest levels for almost 2 years.

- Overall, US inflation remained on a downward trend in November, but at a slower pace than in recent months. Indeed, core inflation stagnated at 4.0% in November, well below the 6%-plus target for 2022, but still well above the Fed's target. We still believe that core inflation will slow to below 3% before mid-2024, but that thereafter, convergence to the 2% target will be slower and will require a sharper slowdown in US growth and employment in the coming months. Against this backdrop, the Fed is unlikely to raise rates further, but should try to convince the markets that it is not ready to cut rates quickly.

- As risk-taking dominated the end-of-year period, it's worth taking a look at the market segments most directly impacted by aggressive monetary tightening, namely credit. Here, we focus on the financial situation of French companies and the various European credit sectors.

- Our view is that we have entered a true default cycle, for the first time since the mid-2010s. This is suggested by the rapid normalization of defaults in 2023, which we were already projecting at the start of the year, after a virtually default-free period.

- We believe that defaults are likely to rise again next year, though not to crisis levels, and that the credit environment will remain durably tighter than in the years 2015-2021, when the ECB had negative rates and injected lots of liquidity.

- However, we believe that the risk of a credit crisis is limited now that interest rates should stop rising, while the solvency and liquidity situation of companies remains fairly healthy overall.

- We expect the economic situation to remain mediocre for another quarter or two, before improving. Against this backdrop, we obviously need to be extremely vigilant when it comes to the riskiest credits. Nevertheless, the carry on less risky corporate bonds (IG) is attractive. And it's now that, with great selectivity, it's possible to build robust portfolios with discounted securities, particularly in less liquid segments such as private debt, to take full advantage of a rebound.

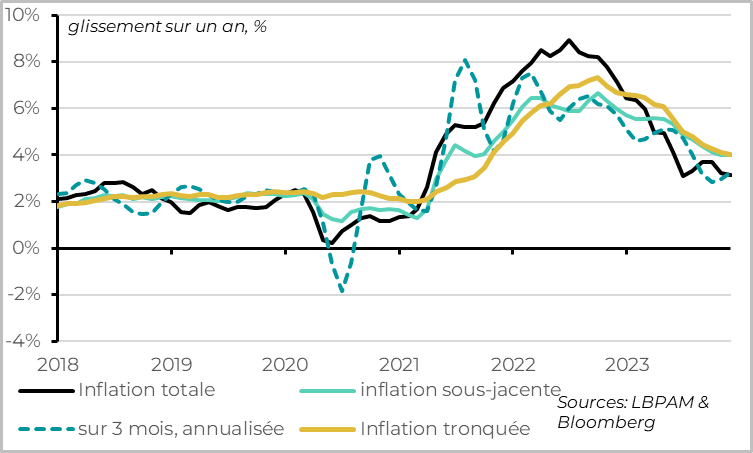

Fig.1 United States: Falling inflation is not a smooth ride

US headline inflation fell from 3.0% to 3.1%, thanks to a further drop in energy prices, even though it reaccelerated slightly on a monthly basis and, above all, core inflation stagnated at 4.0% in November.

Core goods prices fell again in November, for the 6th consecutive month. This was despite a temporary rebound in used car prices over the month. Year-on-year core goods inflation is now at zero for the third consecutive month, and should continue to contribute to disinflation in the coming months, given the slowdown in demand for goods, the normalization of production lines and the fall in energy prices.

By contrast, inflation in services remains more persistent. After slowing slightly in recent months, it stabilized at 5.5% in November, still a very high level.However, rental inflation is gradually slowing from 6.8% to 6.5%, its lowest level for a year and a half.And rental prices are set to slow further in the coming months, given the slowdown in new rental prices over the past year.

In fact, inflation in core services excluding housing, which is closely monitored by the Fed as it is more reflective of trend domestic inflationary pressures, reaccelerated slightly in November to 4.0%. This partly reflects less favorable base effects on prices for services related to tourism and transport, but above all the persistence of domestic inflationary pressures.Indeed, apart from these volatile services, inflation in "super-core" services is still barely slowing down, and remains far too high.

Against this backdrop, with inflation on trend but domestic pressures still too high, the Fed is likely to (1) keep rates unchanged tonight, (2) indicate that the next move on rates may be up or down depending on the data, and (3) if it is a cut, it will not be a quick one. In fact, the economy and, above all, the labour market need to slow down more markedly, and the fall in inflation needs to be confirmed for several more months before the Fed can be confident that inflation will return to target.That said, Fed members are likely to reduce their inflation and key rate forecasts slightly from their very high September forecasts, which may make the Fed's speech more difficult for the markets to read.

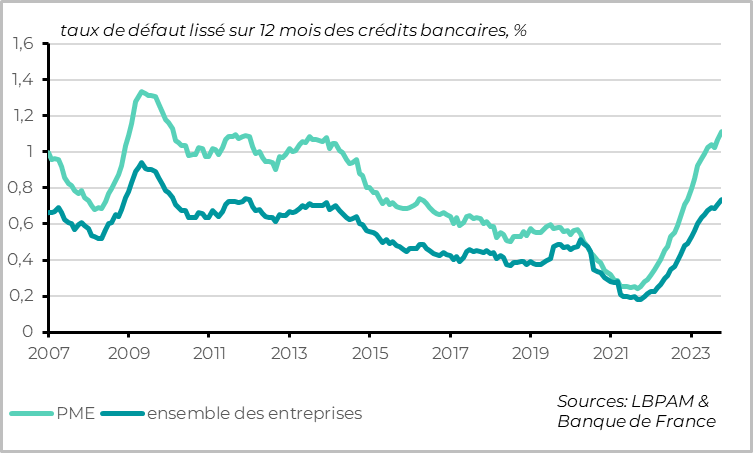

Fig.2 French companies: defaults have normalized rapidly since last year, reaching 10-year highs for SMEs

A real default cycle, for the first time since the mid-2010s. Indeed, this cycle is the consequence of the very restrictive monetary policy (and to a lesser extent fiscal policies) put in place since early 2022 to slow the economy, and thus contrasts with the ultra-accommodative monetary policy of the second half of the 2010s and the exceptional public support during the Covid shock.

The default rate for French SMEs has rebounded sharply from its post-Covid low point. For example, banks' loss rate on business loans has risen back above 0.7% since mid-2023, its highest level for ten years, after dropping below 0.2% in 2021. Similarly, INSEE data indicate that the number of bankrupt SMEs has been fluctuating between 300 and 400 per month since the start of the year, compared with around 100 in 2021, a level only exceeded during the great financial crisis of 2009-2010.

That said, the level of defaults partly represents a catch-up after a period when Covid-related budgetary and regulatory support had artificially reduced bankruptcies. What's more, defaults appear to be particularly concentrated among the smallest SMEs. Defaults for bond-issuing companies, a priori the largest, are rising more gradually and have "only" returned to their pre-Covid average.

But this credit cycle, which should be long, should not be extreme in our view.

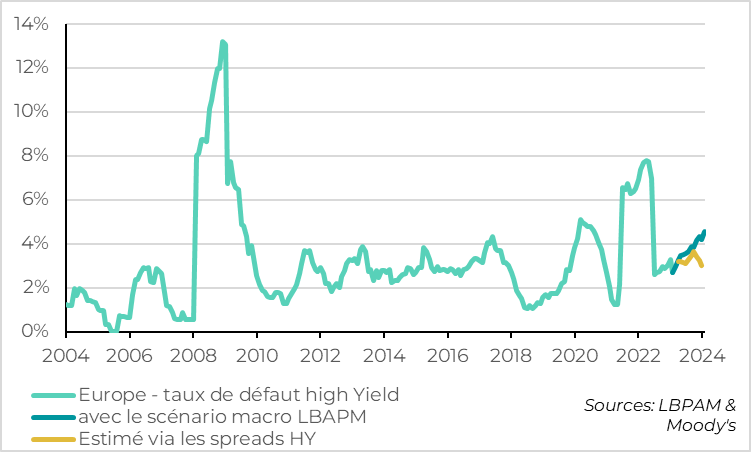

Fig.3 French companies: we expect the gradual rise in defaults to continue for the riskiest companies, without any explosion.

We expect the rise in corporate defaults to continue, although probably less concentrated on SMEs and therefore more widespread. If our macro scenario comes true (i.e. sluggish growth until mid-2024 before a limited recovery, inflation falling towards 2% within a year, and ECB rates gradually falling and remaining higher than before the Covids), we expect European high-yield corporate defaults to rise back towards 4-4.5% next year.

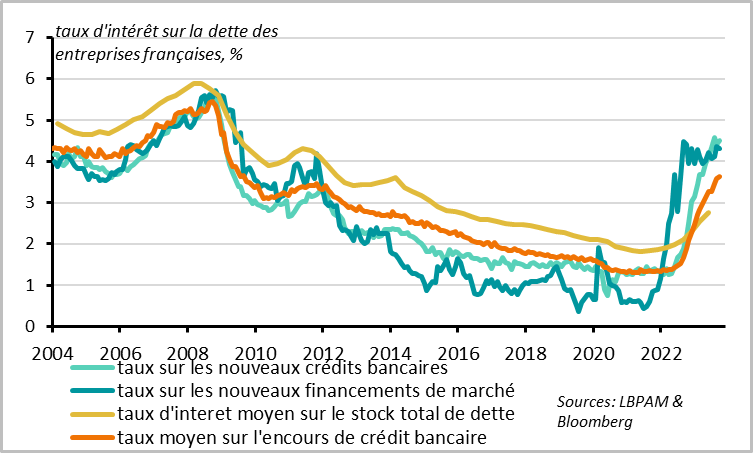

Fig.4 French companies: Lending rates may have peaked but should continue to weigh on business costs

The high interest rate environment is likely to continue to weigh on corporate credit, even though the rates at which companies finance themselves have probably peaked by the end of 2023.

Financing costs have risen sharply since the beginning of 2022, in line with the ECB's rate hike and the normalization of credit risk premiums. Interest rates on both new bank loans and bond financing reached 4.5% by the end of 2023, the highest since the financial crisis of the late 2000s, compared with less than 1.5% just prior to the Covid. Now that the ECB has completed its monetary tightening cycle and may start to lower rates slightly next year, the level of financing costs should stabilize.

That said, we expect financing costs to remain fairly high for the long term. Indeed, ECB rates are likely to remain well above their pre-Covid level (when they were negative), and credit spreads are likely to remain relatively high given the credit cycle.

But corporate financing costs will continue to rise in 2024. The rise in corporate financing costs is transmitted only gradually, depending on the proportion of fixed-rate debt and the refinancing profile of this debt. The average rate on the stock of debt has risen by 1pt since its low point in mid-2023, while rates on new financing have risen by almost 3pt. Interest paid by companies will therefore continue to rise as long as current financing rates remain higher than the average interest rate paid on debt.

It should be noted that the rise in financing costs for bank loans has been faster than for other types of financing, since most of these are at variable rates, and a third are short-term. On the other hand, the bond financing available to larger companies is at fixed rates and often has a longer average maturity. This difference in the transmission of the rise in financing costs may explain the faster rise in defaults among SMEs than among larger companies in 2023. But this difference should fade in the future.

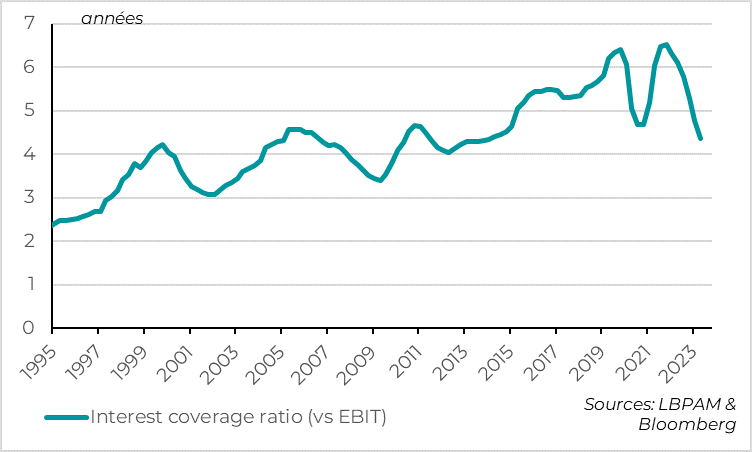

Fig.5 French businesses: companies' ability to meet their financial costs deteriorates compared with the last 10 years, without collapsing

The ability of companies to cover the cost of debt with their revenues, one of the main measures of corporate credit quality, will continue to deteriorate slightly. Indeed, the rise in average financing costs is set to outstrip the increase in profits, which have stagnated this year and are expected to grow only marginally next year. That said, this measure of default risk is likely to return overall to its pre-mid-2010s average level, which would confirm the change in the credit cycle but not necessarily indicate very high risk.

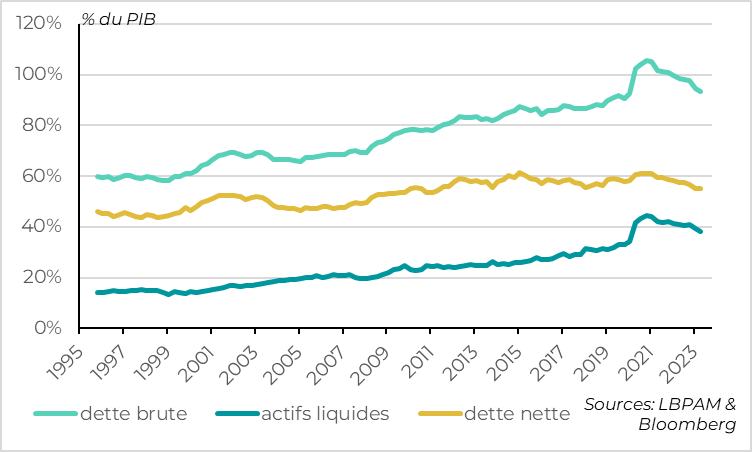

Fig.6 French companies: net indebtedness has fallen slightly over the past 2 years, in parallel with a decline in liquid assets

Above all, the financial situation of French companies remains solid overall, even if their financial flexibility is declining.

Corporate net debt is back slightly below its pre-Covid level. And, unlike the periods that preceded a sharp rise in defaults (the early 2000s or the financial crisis of the late 2000s), corporate debt is not on an upward trend, but is stable overall.

Faced with the high cost of debt, companies have limited their demand for additional financing (see below). In addition, they have used their high post-Covid cash position to reduce their debt levels. Leverage therefore remains under control.

That said, free cash flow is back in line with its long-term trend, which should limit companies' ability to reduce debt in the future.

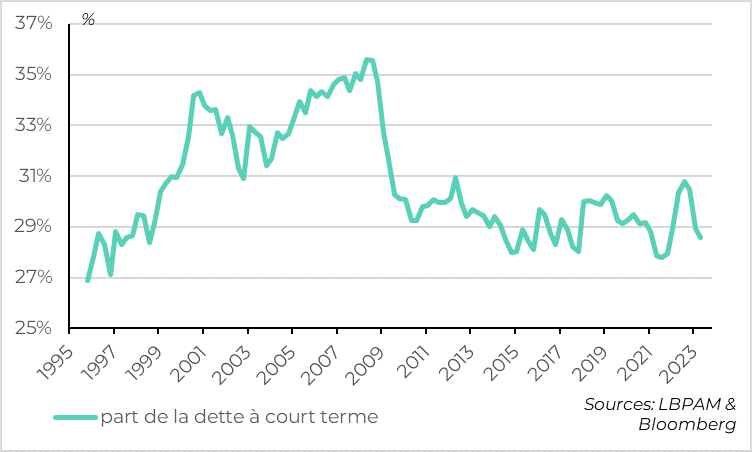

Fig.7 French companies: Overall refinancing risk remains contained for 2024

Companies have maintained a fairly healthy debt profile, limiting liquidity risk. Less than a third of corporate debt matures within a year, which is in line with the pre-Covid period and well below the pre-financial crisis period. Looking at the corporate bond market, the need for refinancing remains relatively limited in 2024, but will increase sharply in 2025-2026.

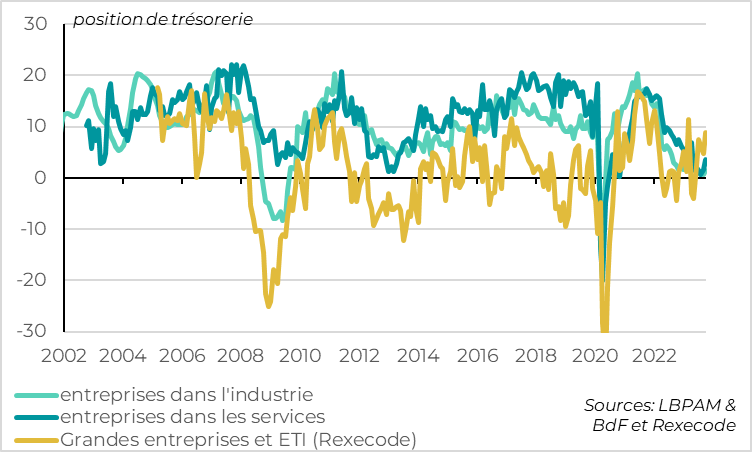

Fig.8 French companies: cash flow stabilizes after a sharp deterioration over the past 2 years

This is consistent with the stabilization of companies' cash positions, albeit at a limited level. After a marked deterioration in companies' cash positions in 2022 and early 2023, the stabilization of profits and corporate prudence has enabled their cash positions to stabilize since the summer, according to the Banque de France survey. This stabilization is particularly marked for larger companies, according to the Rexecode survey, but is fairly widespread in terms of sector and company size.

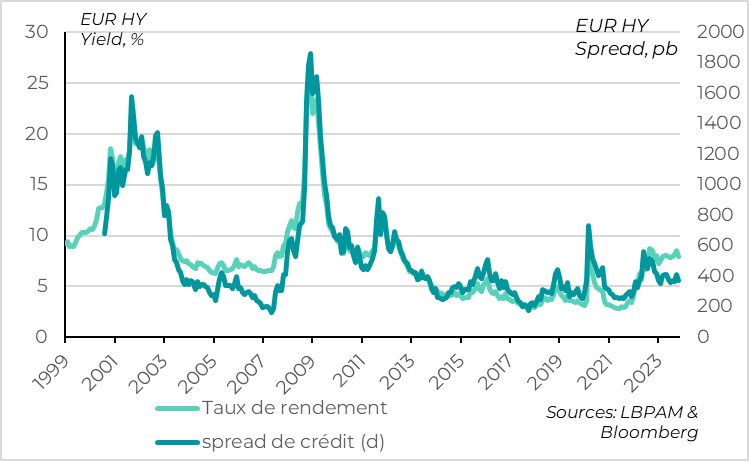

Fig.9 Risky Eurozone companies: relatively attractive yields

Faced with a scenario of a controlled rise in defaults, the question for investors is the level of remuneration for this risk.

We believe that investment-grade corporate bonds offer attractive returns at limited risk. As long as defaults don't explode, default risk in this segment is very low. Now, for the first time in 15 years, this market segment is offering a yield in excess of 4%. With risk-free rates expected to fall slightly and credit spreads to remain stable, we are overweight this asset class.

On riskier corporate bonds (High Yield), we need to be more cautious. Admittedly, the yield offered has been stable at nearly 7% for the past year, which seems attractive. But this partly reflects the rise in risk-free rates. Remuneration for default risk is only in line with its average level in the years preceding the covid, which seems relatively low in the context of a more pronounced credit cycle. As shown in chart 2 above, we believe that the current credit spread is consistent with a default rate of 3-3.5%, slightly above its current level and below the level we are projecting. In this context, we are underweight the asset class and, above all, highly selective.

Compared with high-yield credit, a comparable asset class is private credit. But this one seems to us to be a little more attractive. Private credit is also exposed to higher default risks in the period ahead. It therefore also requires a high degree of selectivity, especially given the lower liquidity in this market. However, against the backdrop of a more complicated credit cycle, the advantages of private credit over high-yield bonds are gaining in importance. Indeed, the special relationship between lender and borrower, the ability to fine-tune credit terms and a more diversified pool of potential issuers are attractive. For example, there are fewer than 50 French companies issuing High Yield bonds, whereas private credit offers exposure to a much wider universe and a large number of sectors. What's more, the risk/return offered by private credit is attractive at a time when competing financing offers for companies are constrained (bank loans, syndicated loans, etc.), making it possible to negotiate attractive terms for the private lender, especially over a long time horizon.