Without trust, fear creeps in

Link

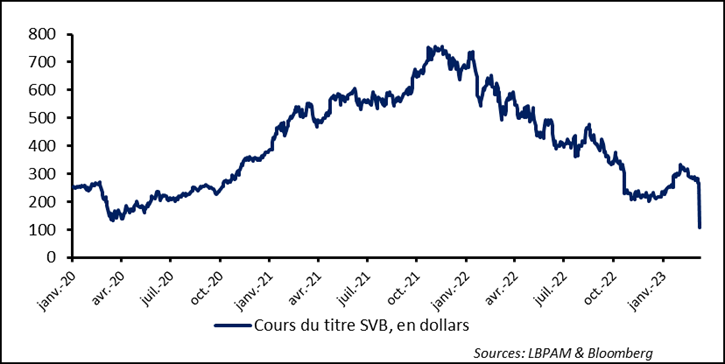

- The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) went bankrupt spectacularly in a matter of days. It was closed on Friday evening. The speed of its collapse was generated by the greatest danger that a banking institution can face, the loss of trust. Faced with announcements of potential large losses and a possible increase in capital, the depositors of this essential bank in the tech ecosystem took fright and began to withdraw their assets. A wave of panic set in and SVB's share price plunged. The panic was all the more sweeping as a few days earlier, Silvergate, associated with the financing of fintech, particularly crypto-currency traders, went bankrupt. To amplify this wave of fear even further, Signature Bank, which specialized in digital financing, collapsed in New York. As expected, this shockwave strongly affected investor behaviour. Bank stocks triggered a fall in American stock exchanges, but also of other stock markets around the world, while people sought refuge in government bonds. This in turn led to a sharp fall in yields.

- As is well known, it is essential in such a situation for the public authorities to restore trust and confidence in the banking system at all costs. In this sense, whereas, as per the usual procedure, the SVB was transferred to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the latter, together with the US Treasury and the Fed took swift action over the weekend with a joint statement intended to calm the markets. It was accordingly announced that all SVB and Signature Bank depositors would be able to access their deposits as of Monday. This is intended to reassure depositors of all banking institutions. In addition, the Fed has made additional financial resources available to any eligible bank to meet the needs of its depositors. These measures should restore calm, especially since, as the Fed claims, the banking system as a whole is well capitalized and therefore capable of facing cyclical adversities.

-

Order should therefore return to the markets as of Monday, as we see it. This incident is however likely to have some after-effects and a risk premium on possible unanticipated fragilities might well appear in the banking world. The measures already taken by the authorities nevertheless show a vital determination to avoid any systemic risk, i.e. any accident that would paralyse the financial system. Questions about the regulation of certain banking entities are bound to surface, of course. Similarly, questions will arise about the transparency of the accounts of banking institutions, which would make it possible to better anticipate mismanagement. Furthermore, the fact that the bankruptcies that have just occurred are all in the technology sector seems to indicate that the financing of this segment of the economy, which benefited enormously from the period when the cost of credit was extremely low, may be weakened. Finally, in this phase of very rapid monetary tightening, the Fed, like other central banks, may be concerned about the possibility of other financial risks emerging. This consideration has surely always been present, but this episode could give it even more importance.

-

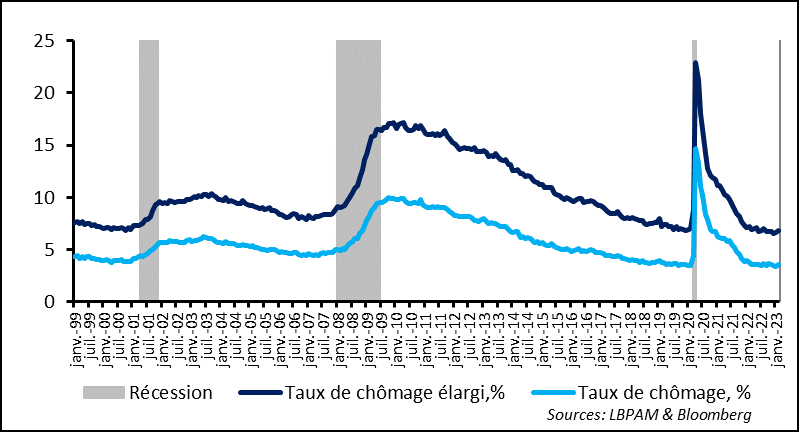

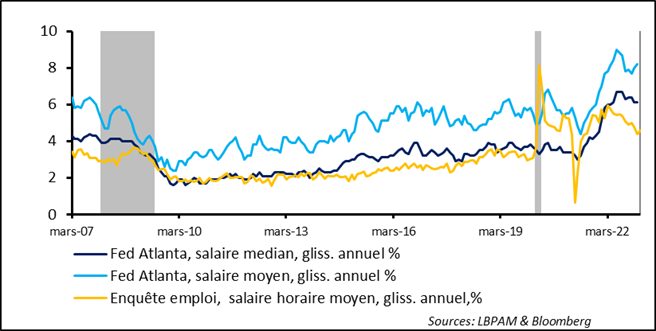

Released in the midst of this banking turmoil, the US employment report for February was rather mixed, but it confirmed that the labour market remained strong. Thus, 311,000 new jobs were created during the period according to the survey conducted among companies. This was higher than expected, but below the spectacular 517,000 of the previous month. The US economy therefore continues to create jobs in a big way. At the same time, according to the household survey, the unemployment rate rose slightly to 3.6%, after a historically low of 3.4% in January, but is still at its lowest level in over 50 years. Furthermore, average hourly earnings, while accelerating on an annualized basis, have decelerated in monthly terms. This deceleration in wages can be viewed in a positive guise by the Fed, even if it favours other measures of wages less affected by compositional effects. As we see it, these data, not to mention the episode of financial turmoil, still point to a 25-basis point (bp) increase in the Fed's policy rate at its next policy meeting on 21-22 March.

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) went bankrupt spectacularly in a matter of days. It was closed on Friday evening. The FDIC took control. The reason for the bankruptcy was poor management. The SVB played a major role in the financing ecosystem of technology companies in Silicon Valley. In particular, start-ups in the sector and especially venture capitalists would park their deposits in this bank, which also offered them financing. Like any bank, it engaged in processing, i.e. it financed itself in the short term (essentially by relying on a large deposit base) and lent in the long term. In order to earn a margin on the cost of its deposits it bought assets, apparently mainly long-dated fixed-rate US Treasuries.

As we know, the financing of technology start-up grew strongly and the SVB flourished during the long period we have been through, when interest rates were at extremely low levels.

As interest rates have risen over the last year, the increased cost of credit has had a significant impact on the financing of new businesses. In addition, the bank's management of its cash by investing it in long-term, fixed-rate investments has resulted in a massive loss of value of its assets (with interest rates rising sharply, the value of its assets, mainly Treasury bonds, was falling). The managers of the bank's balance sheet seemed to be convinced that interest rates would never rise for long. They were not alone. So as deposits dried up and losses accumulated on its assets, the bank could no longer be viable, especially if its customers withdrew their deposits, as they did. The market realized that the bank could go bankrupt, and the value of the stock collapsed.

Figure 1 United States : The rapid collapse of the SVB with panic setting in as depositors withdrew their assets

So on Friday, the FDIC took control. This is the usual procedure in case of a bankruptcy. The FDIC is tasked with insuring the deposits and therefore with proceeding to sell the bank’s assets in an orderly fashion as quickly as possible. A buyer has apparently been identified already and the bank could reopen in the coming days, but under a different name.

This sequence highlights weaknesses in the financial system, some of which were created during the period of very low interest rates and abundant liquidity. The Fed will in all likelihood have to exercise closer supervision over certain medium and small banks. It also raises questions about the ability of the market, in terms of accounting and transparency rules, to identify early the risks associated with the activities of certain players. It moreover specifically reflects the reduced momentum of the technology sector in this new period when the cost of financing is becoming much higher. In point of fact, today, it seems that after the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), financing is mainly going to the sectors related to the energy transition. Needless to say, care should be taken not to create excesses in the future.

In the short term, as it continues to tighten its monetary policy in order to fight inflation, the Fed is bound to take a little more into account the financial risks that tightening may pose. At this stage, however, the banking sector in general seems to us to be sufficiently capitalized to cope with an economic downturn. In this sense, while calling for caution, this should not alter the path of monetary tightening.

The US employment report for February showed that the labour market remained robust. According to the business survey, the US economy created 311,000 jobs, again more than expected. Nevertheless, job creation is slowing down compared to January's creation of over 500,000 jobs. At the same time, the household survey showed that the unemployment rate increased from 3.4% to 3.6%, which remains one of the lowest rates in 50 years. The rise in the unemployment rate mainly reflects a strong inflow of new people into the labour market, which resulted in a slight increase in the participation rate to 62.5%, still a small percentage point below the pre-pandemic level.

Figure 2 United States : The unemployment rate rose slightly as more people entered the labour market, but remains historically low

The report confirms that the labour market remains very tight overall, with continued strong job creation in sectors that were lagging behind when the economy reopened. This is particularly the case for the catering and leisure sector, which saw jobs grow by more than 100,000 over the month. In contrast, the manufacturing sector, as indicated by the business surveys, is losing jobs for the first time in almost two years.

The persisting strength of the labour market should continue to push some wages up. The statistics on the average hourly wage cost from the survey conducted among companies nonetheless shows that the monthly increase has eased (0.2% compared with 0.3% the previous month), although the year-on-year increase has accelerated (4.6% compared to 4%). As is known, however, these statistics have very large compositional biases which can skew the "true" wage growth. This is all the more the case as wage levels are lower in the sectors that are currently creating the most jobs. We will therefore have to wait for other statistics in the coming weeks to get more precise indications on the trajectory of wages, such as the Atlanta Fed's figures.

Figure 3 United States: Wages are still rising at a place that is inconsistent with 2% inflation.

Despite the good numbers, the jobs report does not seem to show any urgency for the Fed to hit harder. The inflation figures this week will tell us more than the various wage measures to come. We continue to believe that the 25-bp hike remains the most likely outcome.

The tensions created by the financial turmoil of the last few days are understandable, but we do not think that the Fed is about to change course quickly at this stage. Greater caution will surely be needed and the mention of financial risk management could also be emphasized by central bankers, but we do not think that the Fed will adopt a "panic" tone and give a more complacent message on the way to proceed with its monetary policy. We stick to our scenario of continued monetary tightening for some time to combat inflationary pressures.