So far so good

Link

-

The markets continue to position themselves for a perfect scenario. Equities have come back to within 2% of their July highs and long-term yields have returned to their mid-September levels. The markets expect inflation to slow sufficiently to allow key rates to be cut before mid-2024, without growth slowing sharply. These expectations may hold for a few more weeks, given that the latest macroeconomic data point in this direction. But the risk of a sharper slowdown (our scenario) or more persistent inflation could quickly weigh on risky assets. With valuations having risen since the start of the month, the margin for error is limited.

-

The minutes of the Fed's meeting at the beginning of November confirm that the Fed is on pause and wishes to be more cautious now that rates are restrictive and inflation is slowing. That said, the Fed is maintaining a bullish bias, saying it is prepared to do more if inflation does not slow as sharply as expected. In terms of data, US growth has been slowing since October but remains in positive territory according to the Chicago Fed's indicator. That said, the Conference Board's leading indicator continues to point to the risk of a more marked slowdown in the months ahead.

-

Yesterday, the European Commission published its opinion on national budgets for 2024. This is once again important, as the European budgetary rules come back into force next year after a suspension linked to Covid, and because interest rates on public debt have risen sharply.

-

The Commission's generally lenient judgement limits the risk of a financial crisis, not least because it implies that Italy will continue to benefit from implicit ECB support next year. That said, the Commission is already pinpointing the French budget as being "at risk of non-compliance". While this has no impact in the short term, it does underline the fact that France still has a lot of work to do to put its public finances in order in the medium term.

-

While the European budgetary rules emphasise the need to adjust public finances in Europe, this should not obscure the fact that these needs will be far greater in the United States over the next few years.

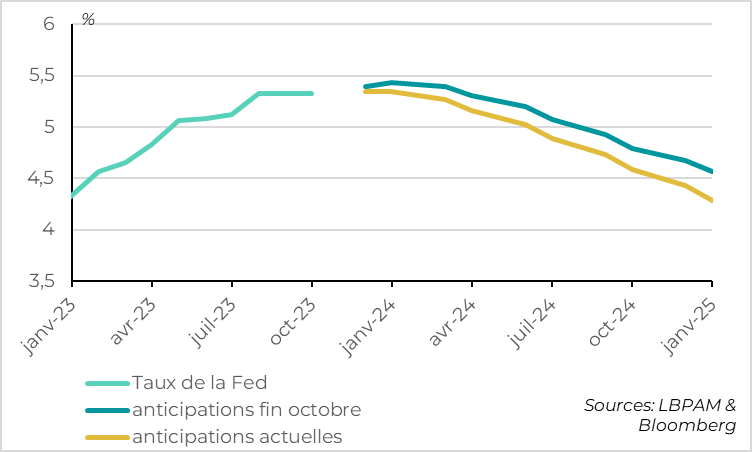

Fig.1 Fed: Markets expect more rate cuts in 2024

The minutes of the November Fed meeting confirmed that Fed members were unanimous in keeping the key rate unchanged and adopting a "cautious approach" now that inflation is slowing sharply and there are signs that restrictive policy is cooling the economy. At the same time, Fed members are maintaining an upward bias on key rates, reiterating that they would do more to control inflation if the data indicated "insufficient progress".

In our view, this confirms that the Fed will remain on hold for the next few months, while it waits to see how the slowdown in inflation and activity plays out. We continue to expect that the Fed could start cutting rates before next summer, but only if the slowdown in the economy and the easing in the labour market are significant. In the short term, we believe that the Fed will continue to say that it is ready to do more, especially as financial conditions have eased significantly since their meeting at the beginning of November. Long-term interest rates have fallen by around 50bp and equity markets are at their highest level since early August.

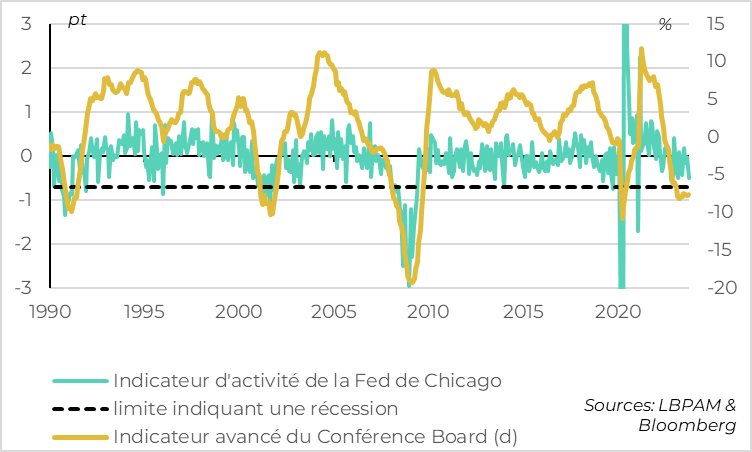

On the activity front, the latest data still point to a slowdown in the US economy after the end of the summer, but a slowdown that is still contained. For example, the Bank of Chicago's activity indicator, which summarises a large number of coincident indicators, fell from 0 to -0.4 in October. This is its lowest level since the first quarter and indicates that growth is falling back below its potential (~2%). But it is still well above the zone that historically indicates a fall in activity (below -0.7pt).

That said, the Conference Board's leading indicator continued to fall rapidly in October (-0.8%). Year-on-year, it has been around -7.5% since the end of 2022. This is well below -4.5%, which is the historical limit that indicates a coming recession. This indicator probably exaggerates the weakness of the outlook in this unusual economic cycle, as it focuses heavily on the situation in the goods sector and on monetary data, which have been badly affected by the Covid shock and the associated aid measures. But it is a reminder that the current signs of a gradual slowdown could well be the first signs of a sharper slowdown in the US economy in the coming months.

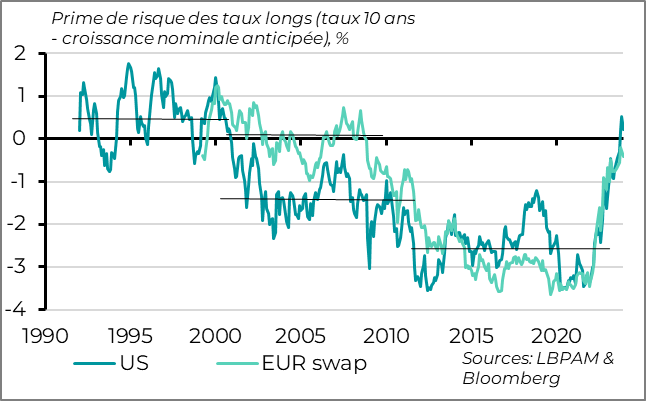

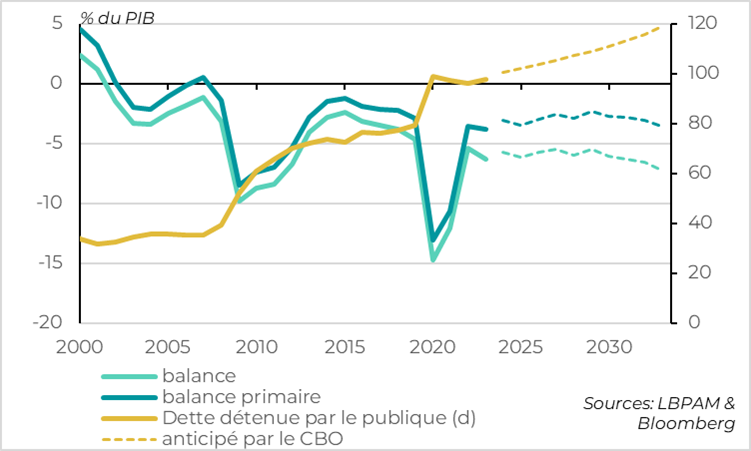

Fig.3 Interest rates: balancing public finances becomes important again in a context of normalised interest rates

For the first time since covid, European budgetary rules will once again become binding from 2024. And quite apart from the legal nature of these rules, it is once again important to balance public finances in a context where interest rates on public debt have returned to the level of medium-term growth. In this context, primary deficits (excluding the cost of debt) need to return to balance in the medium term only if public debt is to be stabilised at its current (high) levels.

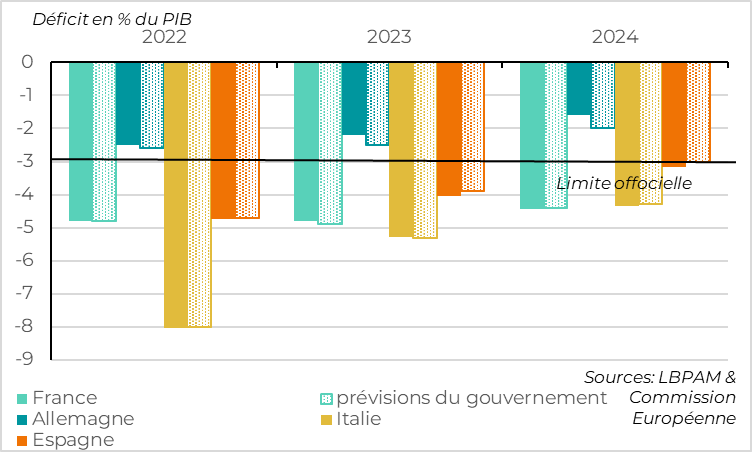

Fig.4 Eurozone: Budget balance forecast by the Commission and the countries

What rules will apply in Europe? Nothing is yet certain. The Commission has proposed new operational rules that are more flexible than the pre-Covid rules. These rules provide, for example, for an adjustment of the trajectory over a horizon of more than 4 years instead of the minimum annual adjustment previously imposed. And the Commission is imposing a limit on primary expenditure growth instead of a structural deficit target. But these rules still have to be accepted by the European Parliament and the Heads of State before the end of the year, otherwise the old, stricter rules will apply in 2024. But some countries are still reluctant to relax the rules

Fig.5 Zone Euro: Opinion de la Commission européenne sur les budgets nationaux 2024

The European Commission has published its first opinion on the budgets of Eurozone countries since Covid. The opinion was published yesterday, and is due to be discussed at the December Eurogroup meeting. Overall, no country is in the worst category, that of serious risk of non-compliance.

The European Commission has singled out France, considering its budget to be at risk of breaching the budgetary rules. This is because the French budget provides for too high a growth in public spending and because not all energy subsidies expire this year. This is also the case for Belgium. Being on this list has no immediate consequences. The Commission is asking these governments to adjust their budgets for 2024, but it is unlikely that France will change them significantly. But it does illustrate that there are still major adjustments to be made over the next few years to avoid a penalty procedure.

Italy is classified as "not fully compliant", along with the Netherlands. The Commission considers that there is a risk that public spending growth will exceed the limit in 2023-2024, even if the budget plans to respect the rule. The Commission is also critical of the fact that Italy is using the reduction in energy-related spending to finance other expenditure, rather than to reduce the deficit.

Germany and Portugal are also in this category, but only because not all of their energy aid measures have expired. The Commission is asking them to stop this aid so as not to exacerbate inflationary pressures and prevent these measures from becoming de facto permanent. However, this ranking does not reflect fears about public finances, since the deficits of these two countries have already fallen below the limit of 3% of GDP by 2023.

Finally, Spain, Ireland and Greece are judged to be in compliance with the rules, demonstrating the adjustment made by these countries, whose public finances have historically been under pressure.

The Commission's lists, if validated by the Eurogroup, will serve as a basis for the Commission to decide whether to launch an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) against a country in the future. This procedure is the sanction procedure in the European Union. This could be the case for countries at risk of compliance if they do not take sufficient measures to comply with the rules.

But the Commission has announced that it will not trigger an EDP before the end of June at the earliest. Judiciously, this means that the European authorities will not ask any country to make a significant budgetary adjustment before the European elections at the beginning of June. Given that no country is considered to be at "serious risk of non-compliance" and that this procedure takes time, it is unlikely that any country will officially be in EDP before the end of 2024.

This is important for financial stability in the Eurozone, because the absence of a PDR is a criterion that the ECB has set itself for being able to buy the public debt of a country under attack (via the emergency TIP programme). This reduces the risk of a debt crisis in the coming months, despite the difficult context (lower growth, higher financing costs and lower debt held by the ECB). All in all, we believe that sovereign yield spreads between countries should remain high, but not explode.

Fig.6 United States: deficits still twice those of the Eurozone, and debt on an upward trajectory

The European budgetary rules highlight the budgetary risk in Europe, but they should not obscure the fact that the budgetary situation is much worse in the United States. The budgetary adjustment to be made after the next presidential elections is very important.

The Commission estimates that the deficit has been reduced in 2023 from 3.6% to 3.2% of GDP and that it will fall back below 3% of GDP in 2024 (to 2.8%). However, this is still well above its pre-Covid level, when it was below 1%. In addition, the Commission expects public debt to remain stable or fall slightly in all countries whose debt exceeds 60%.

In contrast, the US federal deficit has widened from 5.4% to 6.3% of GDP this year, and should remain close to 6% in 2024 and 2025. Furthermore, while public debt remains high in the Eurozone, stabilising at around 90%, it is approaching 100% in the United States and is set to rise further in the coming years.