The Fed faces the dilemma of strong growth and disinflation

Link

-

While the CAC index rebounded strongly at the end of last week on the back of good results from LVMH, and most European indices also posted solid gains, the US stock market took a breather. This can be partly explained by the good economic figures from across the Atlantic, which could make the Fed more wait-and-see about rate cuts than the market was anticipating.

-

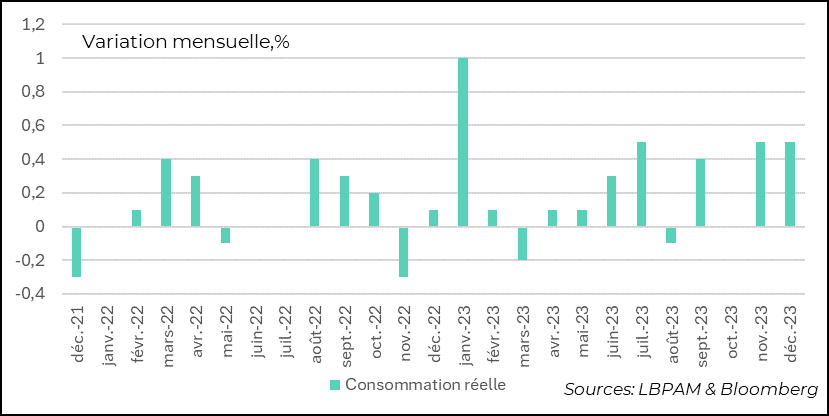

Indeed, following the much stronger-than-anticipated GDP figures, the publication of monthly consumption statistics showed not only that consumption had been very robust in December (0.5% in real terms), but also that momentum in November had been stronger than previously estimated (0.5% vs. 0.3%). With incomes growing at a slower pace, the savings rate (3.7%) also fell again, to its lowest level since the end of 2022.

-

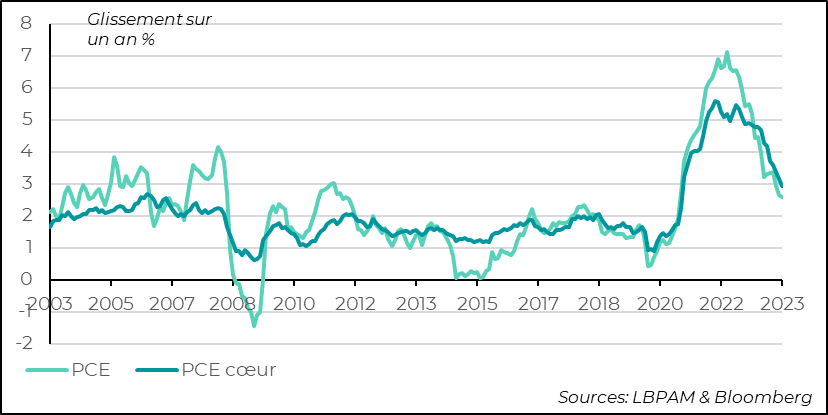

On the inflation front, the PCE consumer deflator, the Fed's preferred measure, was unchanged in December from the previous month at 2.6% year-on-year, but excluding energy and food, decelerated to 2.9% from 3.2% in November.

-

In recent months, inflation has indeed continued to decelerate, which should give the Fed cause for confidence. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to separate the effects associated with the disappearance of temporary factors from those that are not. This week, we'll see whether the Fed thinks its battle against inflation has been won, or whether it's remaining more cautious. We think that, given the robustness of the economy, it should be patient.

-

Tensions in the Middle East remain high. An oil tanker was hit by fire from Houthi rebels, exacerbating the difficulties of shipping close to the Red Sea. Continued insecurity is likely to increase transport costs and create supply problems. Also, a US army base in Jordan close to the Syrian border was attacked. 3 soldiers were killed and more than 20 wounded. The Americans indicated that the perpetrators belonged to an Iranian-backed militia, and President Biden declared that the United States would retaliate.

The American consumer remains the bedrock of growth in the US economy, as demonstrated by its contribution to strong GDP growth in 4Q23. Monthly household consumption data showed that not only was growth very strong in December, but also in November. In fact, the end of the year saw some of the strongest two-month growth in household spending in the last 3 years.

Fig.1 United States: Household spending accelerates sharply at year-end

-Actual consumption

The continuing strength of the labor market is one of the factors contributing to this solidity of consumption. Indeed, the unemployment rate remains low (3.7%) and wages are still rising at a brisk pace, even if they have decelerated since their peak.

Also, since the beginning of last autumn, financial conditions have eased considerably, notably through rising asset prices, thus helping to improve household wealth. This was one of the factors contributing to the upturn in household confidence over the last month, as shown by the University of Michigan survey.

At the same time, household spending once again outstripped income growth. As a result, the savings rate has fallen once again. Household net indebtedness is rising, and the savings surplus that seems to have persisted since the large public transfer they received at the time of the covid is drying up.

Fig.2 United States: Savings rate continues to fall

-Savings rate, %

This favorable effect of past savings is likely to fade by 2024.

Nevertheless, we can only note that for the time being, spending momentum remains strong, which could continue to sustain growth for longer than we thought.

What will determine the dynamics of household growth will essentially be the situation on the job market. Here again, we can see that even if employment growth is decelerating, it is still robust enough to sustain consumer appetite.

The December employment report, to be published this week, will give us a further indication of the robustness of job creation. On the layoff front, data on jobless claims remain very weak, suggesting that companies are not inclined to reduce their payrolls, particularly in a context of resilient growth.

Inflation figures continue to be eagerly awaited each month to determine whether the Fed can begin to loosen its monetary policy quickly.

Inflation as measured by the consumer deflator, the PCE, was, as expected, stable in December at 2.6% year-on-year. Nevertheless, core inflation, i.e. excluding energy and food, decelerated to 2.9% from 3.2%, slightly higher than expected.

The trend in inflation is therefore still towards deceleration. It has even been a little faster in recent months than might have been expected.

Fig.3 United States: Core inflation continues to decelerate in December, falling below 3% year-on-year

-PCE

-PCE heart

For some, it's clear that inflation has been beaten and that the road to the 2% target is well underway. Indeed, the very short-term measures, i.e. the 3-month or 6-month inflation trend, show an even more favorable dynamic, with inflation below 2%.

Nevertheless, it remains very difficult to completely separate the dissipation of temporary effects, which have been considerable due to the constraints generated by the Covid (bottlenecks) or due to the war in Ukraine, from the effects linked to overheating generated by the excess demand provoked by public aid.

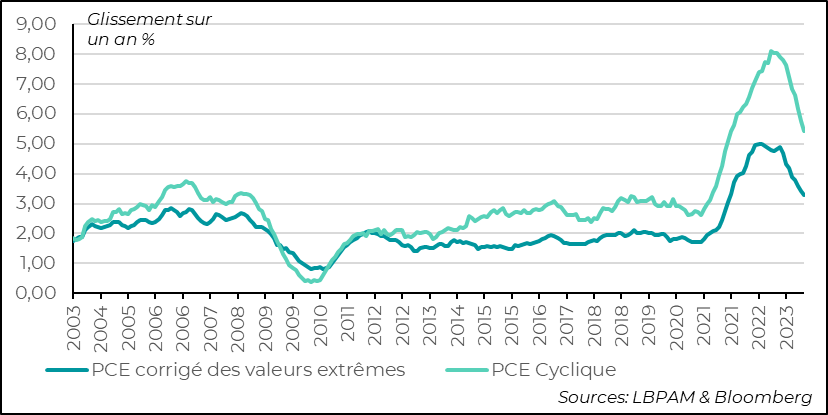

It's true that even measures that attempt to separate extreme effects or more cyclical dynamics (i.e., more related to overheating) are decelerating. This is obviously positive. Nevertheless, these measures remain at very high levels. Such is the case with the Cleveland Fed's measure, which extracts the prices whose variations are the most extreme, or the San Francisco Fed's, which constructs an index by taking the basket of goods and services most correlated with the economic cycle.

Fig.4 United States: Trend measures point to a deceleration in inflation, but remain high

-PCE corrected for extreme values

-PCE cyclic

It still seems to us that the idea of seeing the inflationary episode as the result of supply shocks is too narrow. The impetus given by public policies across the Atlantic was so massive, and in part still persists, that it's hard to believe that the impact on inflation will dissipate quickly.

At the same time, the Fed's sharp rate hike has surely helped to curb inflation, even as the temporary effects were dissipating. Nevertheless, it is clear that the impact on growth has been weak. In particular, the impact on financial conditions, as a driver of monetary policy transmission, is equally weak. Today, financial conditions are the most flexible they have been since the summer or mid-2022.

This leads us to believe that the acceleration of some inflation, notably in services, will not dissipate so quickly. Much will depend on wage trends. It remains to be seen whether the labor market will ease further and/or whether the disinflation already achieved will strongly moderate wage increases in the months ahead.

The most important thing for everyone, and for the markets, is obviously the Fed's diagnosis. We believe that, given the robustness of growth, and therefore the lack of restraint that seems to be coming from monetary policy today, the Fed will be more cautious in easing its policy. Obviously, if the pace of disinflation persists unabated, it will have to act.

However, the Fed, perhaps spurred on by Chairman Jay Powell, may decide that it believes disinflation is here to stay and that it's time to adjust policy. That would be a risk. Will it take it?