A robust Chinese recovery, albeit an atypical one

Link

- The markets were relatively stable early this week, with both bonds and equities tentative in the wake of last week’s gains. Actually, they are tentative in the run-up to the first-quarter US reporting season, given that the first numbers are slightly better than expected but are widely dispersed and contain lots of uncertainties on the outlook for the coming quarters. Meanwhile, the markets are beginning to raise their forecasts of Fed and ECB key rates, although their expectations remain well below [H1] their levels prior to the mid-March episode of bank stress.

- The Chinese recovery did indeed occur, driven by consumption. Growth reaccelerated sharply in Q1, from 2.9% at end-2022 to 4.5%, driven by a robust recovery in services and consumption. This reflects the cyclical rebound made possible by the reopening of the economy, which should become more pronounced in Q2 and open the door to growth far stronger than the official 5% target for this year. That’s why we continue to tactically overweight Chinese equities.

- That being said, business investment is still weak in China, with the stabilisation of the real-estate sector still to be confirmed, and a tentative recovery in manufacturing activity. This Chinese recovery is therefore different from previous cycles, which were driven by public stimulus in favour of real estate and infrastructure. This calls forth two remarks. First, the Chinese recovery may turn out to be a mere blip as long as it is not driven by a more normal trend in consumption, given that employment and household income are still sluggish. Second, the knock-on effect of this recovery in Chinese domestic demand may, on the whole, be more limited and, more importantly, could benefit different sectors than in the past (consumer goods instead of capital goods, and service providers rather than commodities, etc.).

- Job markets are beginning to cool off a bit in developed economies on both sides of the Atlantic but are still overheated, and this is driving still-high wage growth. In the United Kingdom, for example, the unemployment rate began to rise slightly in February (from 3.7% to 3.8%), and the number of vacant jobs has been falling for 10 months, but the number of vacant jobs per unemployed person remains at levels never seen prior to Covid. Wage growth is still not slowing and, at 6.6% year-on-year, remains too high to hope for a rapid and sustainable easing in inflationary pressures in services. The situation is similar in the United States, where wage growth sped back up to 6.4% in March, according to Atlanta Fed data. In the euro zone, wages have even continued to accelerate in early 2023, albeit from a lower base.

- For central banks, this suggests that their monetary tightening is beginning to pay off, but that they must keep their policies at least as restrictive until wage growth begins to slow sufficiently. We expect the Fed, the ECB and the BoE to pause their rate hikes by this summer but don’t expect them to lower their rates until at least 2024. For that to happen, economic growth must remain weak in the coming quarters. Hence, our cautious stance on the riskiest assets.

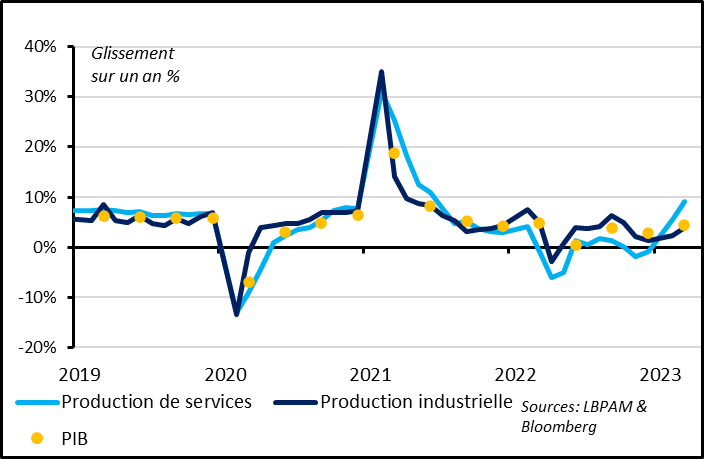

Fig. 1 – China: Growth reaccelerated robustly in Q1, driven by services

Chinese GDP growth has reaccelerated more than had been expected in early 2023, from 2.9% at end-2022 to 4.5% year-on-year. This is a one-year high, and growth should speed up even more in Q2, owing to the weakness in economic activity during the Shanghai lockdown one year ago and the continued pick-up of activity in March. This almost guarantees that Chinese growth will exceed the official 5% target for this year.

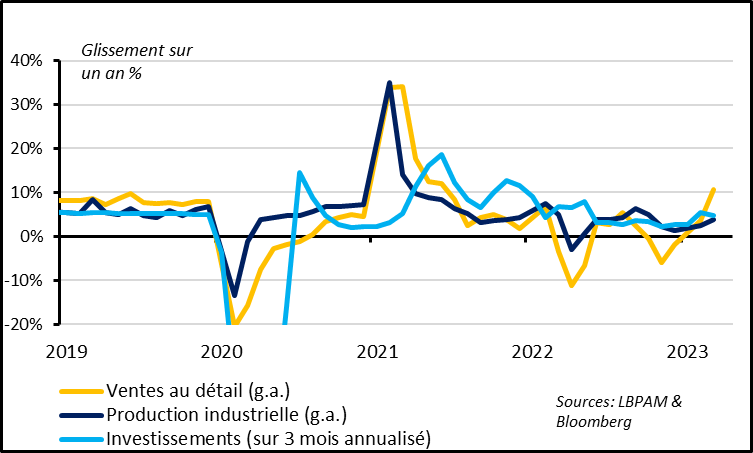

The recovery is being driven by domestic demand, which makes sense, given the reopening of the economy and amount of savings accumulated by households. On the demand side, consumption accounted for two thirds of GDP growth in Q1, and retail sales sped up sharply in March, to 10.6% after 3.5% in January/February. On the supply side, services accounted for 70% of GDP growth in Q1 and accelerated to 9.2% in March, a high since 2021.

Year-on-year % chg.

Retail sales (YoY) Manufacturing output (YoY) Investment (3-months annualised)

However, manufacturing output is recovering more slowly[H1] , at 3.9% in March vs. 2.4% in January/February. This is consistent with the outlook for weaker external demand following the March rebound in exports and also with the stubborn weakness in business investment. Indeed, investment spending in value terms stayed at the same pace in Q1 (at 5.1%). In particular, real-estate investment once again made a negative contribution to growth in early 2023, despite the levelling off of property prices and a slight uptick in sales. This suggests that real-estate investment will stabilise only gradually.

All in all, China’s cyclical recovery is on track and should drive strong growth in 2023, and that is why we are overweighting of Chinese risky assets. However, there is no firm guarantee that the rebound in consumption will outlast the coming quarters, given the lacklustre growth in employment and household income. Barring a strong recovery in real-estate and infrastructure investment, growth could slow once again in 2024. So further caution is in order regarding China’s medium-term outlook. This is why Chinese officials are saying that the recovery “is not yet solid”.

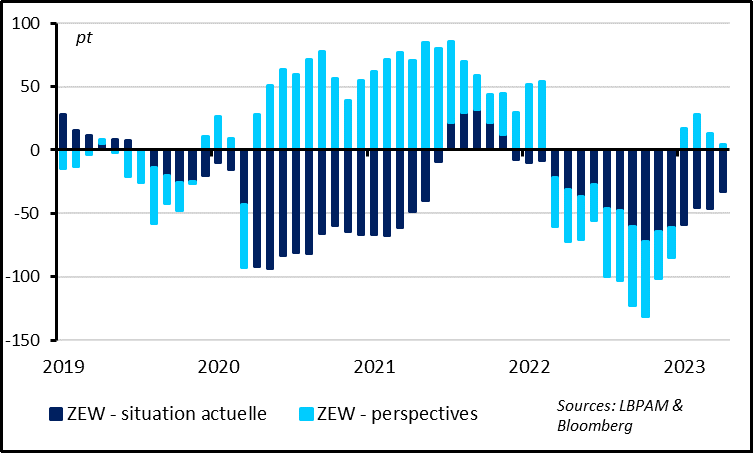

Fig. 3 – Germany: Confidence in the future outlook has fallen over the past two months

ZEW: current conditions ZEW economic sentiment

Investors believe that the German economy will move back to normal in April after a pause in March but are less confident in the outlook thereafter, according to the ZEW survey. The current conditions component of the survey was still in negative territory for April but did rise back to -32.5pt, a high since mid-2022. This suggests that growth will remain weak but less negative than in late 2022 (German GDP shrank by 0.4% in Q4). However, the economic sentiment component fell for the second consecutive month in April and is just barely in positive territory (at 4.1pt). While the March decline was driven by uncertainty over the banks, the weaker confidence in April appears to be related more to the end of energy price declines over the past months and to the impact of the ECB’s ongoing tightening cycle.

Although the ZEW is not the best leading indicator of the German economy (it’s a survey of investors, rather than companies), its decline suggests little prospect for a rebound in growth, which is in line with our scenario of positive but weak growth in the euro zone in the coming quarters.

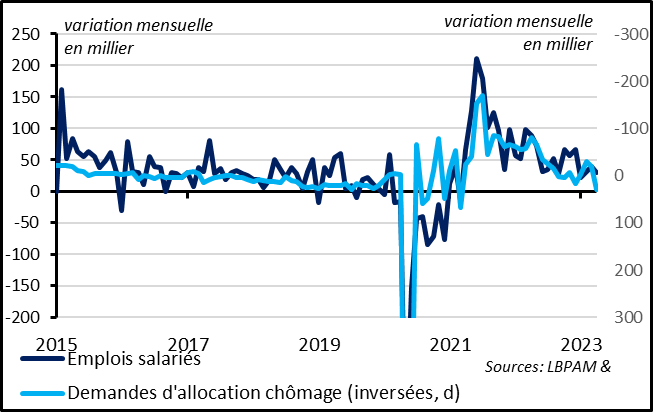

Fig. 4 – United Kingdom: the job market is slowing gradually

MoM chg. (‘000) Salaried jobs Jobless claims (inverted right-hand scale)

The UK jobs reports point to a gradual slowing in the job market, which nonetheless remains too tight. This shows that the BoE’s monetary tightening is beginning to weigh on growth. Although the UK economy held up better than expected this winter, the outlook remains lacklustre, now that reopening-related stimulus and the reduced energy shock are mostly behind us and now that fiscal assistance will be reduced.

Growth in employment is slowing a bit while remaining positive. Salaried employment rose by 31 per mille in March and by 34 per mille on average in Q1. This is the slowest pace of job creations since the start of the post-Covid recovery, although this pace is in line with its trend.

This has caused a slight easing in the job market. As a result, the unemployment rate rose in February from 3.7% to 3.8%, a high since mid-2022. And the increase in the number of jobless workers in March and the gradual decrease in the number of vacant jobs suggests that the unemployment rate will continue rising in the coming months.

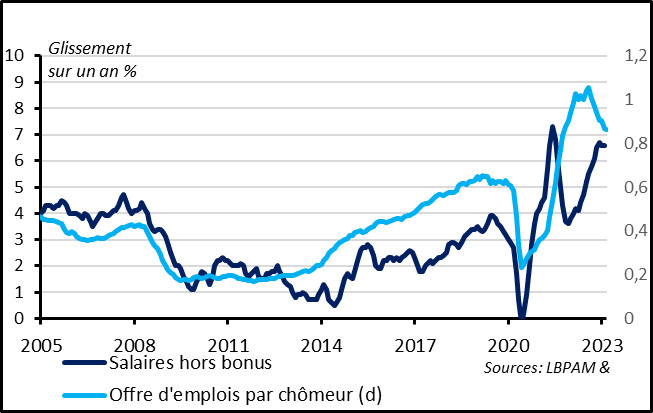

Fig. 5 – United Kingdom: Wage growth is still not slowing, as the job market remains tight

Year-on-year % chg. Wages ex bonuses Job offers per unemployed person (rhs)

However, although easing slightly, the job market is still overheated, and this is maintaining high wage pressures and, hence, high inflationary pressures. That’s why the average weekly wage (without bonuses) rose by 6.6% in February year-on-year, as much as in recent months, although the consensus had expected it to slow to 6.2% (due to more favourable basis effects).

At 3.8%, the unemployment rate has merely returned to its pre-Covid level, which had been historically low and below the equilibrium rate estimated by the BoE (which is above 4%). Moreover, the ratio of vacant jobs is at a one-and-a-half-year low but is still higher than its pre-Covid highs.

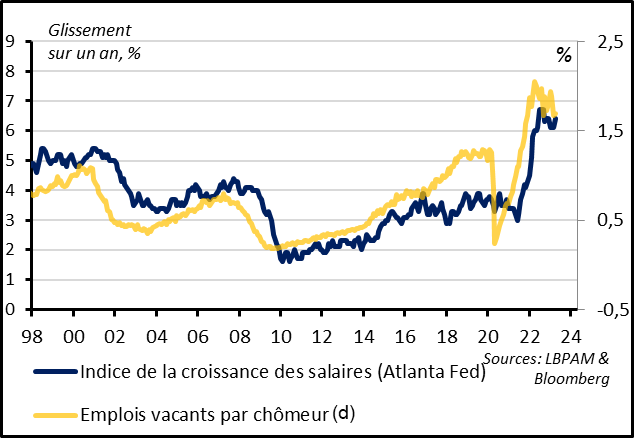

All in all, as in the US (and in the euro zone, although first-quarter data are not available), the ratio of vacant jobs per jobless person in the UK has declined slightly over the past few months but remains at levels never seen prior to Covid. And wages have not begun to slow (and are even accelerating in the euro zone) and remain too high to hope for inflation in services to converge rapidly towards the target rates. For example, in the US, the Atlanta Fed’s measure of wage growth sped back up in March at 6.4% (unlike the less precise measure of hourly income published with the jobs reports).

Fig. 6 – US: No appreciable slowdown in wage growth in March, either

Year-on-year % chg.

Atlanta Fed wage growth index Job openings per unemployed person

Regarding monetary policy, data show that overheated job markets are beginning to cool off slightly from their extreme levels of early 2022. This suggests that monetary tightening is beginning to have an impact, but that policies will have to remain at least as restrictive for a long time to come for tensions in employment, and then in wages, to ease sufficiently. This should then allow core inflation to slow gradually but sustainably.

This is consistent with the latest language by central banks and with our scenario that key rates will stop rising by this summer but will have to be kept high at least until 2024. Market expectations for the ECB and BoE are rather in line with our scenario but are still very low for the Fed. And the economy and employment will have to cool off sufficiently by then for inflation pressures to subside towards more reasonable levels. Otherwise, central banks will have to tighten the screws even more.