What is the right level for long rates?

23.08.2023

Link

- The markets were a little calmer at the start of the week after their sharp decline over the past month (-4.5% for equities), in the absence of any major economic data and in anticipation of the Jackson Hole symposium at the end of the week (the Fed's major annual conference).

- The calendar will intensify between now and the end of the week, with the publication of the first activity surveys for August (leading PMIs, IFO...) and the speeches of the main central bankers from Friday (Powell, Lagarde...). We expect the economic performance gap between the US and the Eurozone to be confirmed but not widened this summer, and for the central bankers to deliver balanced speeches. In the case of the Fed and the ECB, they should indicate that rate hikes are probably behind us, but that key rates will have to remain high for a long time to come.

- The most striking movement over the past month, and the most significant for all assets and geographies, has been the rise in US interest rates. The 10-year yield is at its highest level since 2007, at 4.33%. And this reflects a rise in real rates rather than inflation expectations, which is weighing on other assets. The yield on 10-year inflation-indexed bonds is over 2% for the first time in 15 years.

- In addition to the increase in debt issuance, the main reason for the rise in rates this summer is the resilience of the US economy, despite more than a year of abrupt monetary tightening. This reduces expectations of rate cuts in the coming quarters, and raises fears that the level of rates needed to keep the economy in balance (what economists call the "neutral rate") may be higher than previously thought.

- In terms of valuation, short rates are broadly in line with the Fed's June forecasts, which seems reasonable to us for the time being. As for long rates, there is a great deal of uncertainty and debate as to their reasonable level in the new post-Covid economic regime. But overall, valuations are at least back to where they were before the financial crisis 15 years ago, which seems to us rather attractive. Interest rates in Europe have risen less this summer and offer slightly less attractive valuations, hence our more neutral view on European government bonds and our preference for shorter maturities.

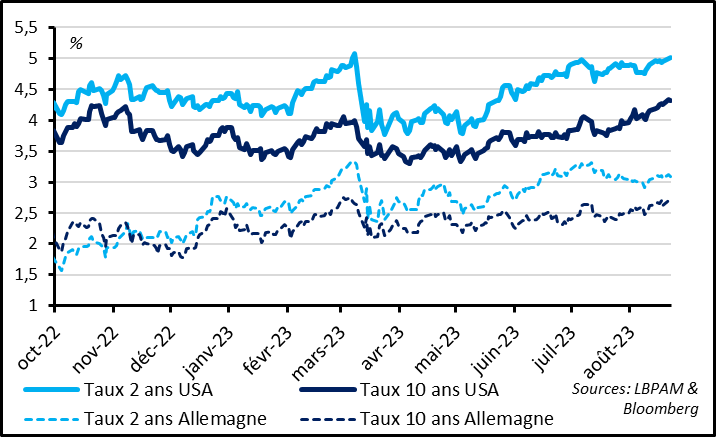

Fig.1 Long-term rates: US long rates have passed their 2022 peak

2-year rate USA - 10-year rate USA

2-year rate Germany - 10-year rate Germany

U.S. yields rose sharply this summer, with the 2-year rate returning to its early March level above 5% and the 10-year rate climbing back above its 2022 highs to reach its highest level since 2007 at 4.33%.

Outside the U.S., Japanese interest rates also rose sharply after the central bank "authorized" long rates to go as high as 1%, compared with 0.5% previously. At 0.65%, the Japanese 10-year yield is at a 10-year high. This exit, albeit gradual, from the Bank of Japan's ultra-accommodative monetary policy is likely to play a significant role in the rise in global interest rates, as it pushes Japanese investors to repatriate part of their bond investments and makes the very popular strategy of borrowing in yen to invest in foreign bonds more expensive.

Eurozone rates also rose this summer, but to a more limited extent, suggesting that their increase reflects the spread of rising US rates rather than domestic factors.

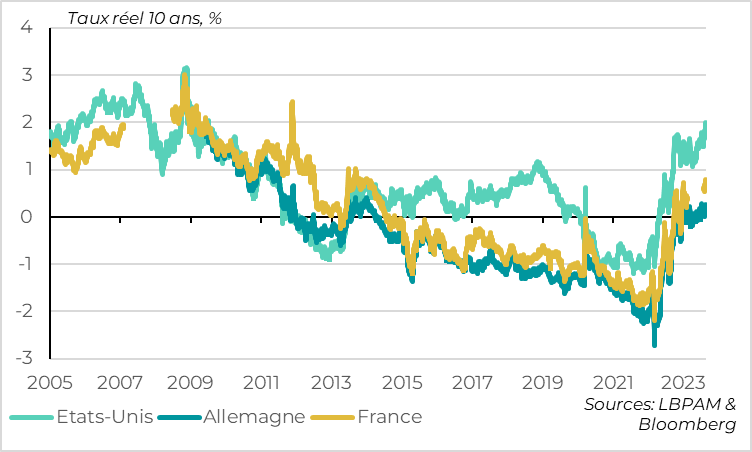

Fig.2 Long-term rates: Real long-term rates exceed 2% in the USA for the first time since 2007, and remain more limited in Europe

10-year real rate, %.

United States - Germany - France

The rise in US yields this summer was due to a rise in real yields, rather than a rise in inflation expectations. As a result, the yield on 10-year inflation-indexed bonds exceeded 2% for the first time in 15 years. Real rates have also risen slightly in the Eurozone, but again to a more limited extent. The German 10-year real yield reached 0.25%, still below its level at the end of 2022.

The rise in US real rates is partly explained by specific factors (higher issuance, higher Japanese rates), but mainly by the resilience of the US economy, despite more than a year of abrupt monetary tightening. This reduces expectations of a rate cut in the coming quarters, and raises fears that the level of interest rates needed to keep the economy in balance (what economists call the "neutral rate") may be higher than previously thought.

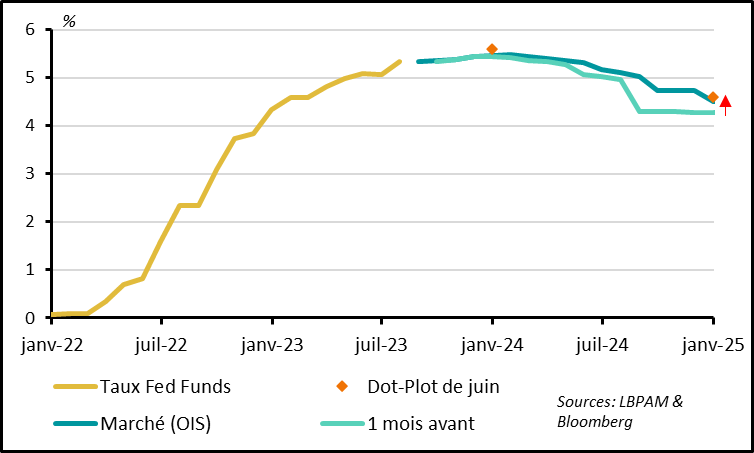

Fig.3 US key rates: markets expect fewer Fed rate cuts in the coming years.

For short rates, Fed rate expectations for the next few years are now broadly in line with the Fed's June forecasts, which seems reasonable to us. The markets are now aligned with our view that the Fed is probably done with rate hikes, but is likely to keep rates elevated until at least mid-2024.

As long as the economy remains as resilient as it is at present, we can't rule out the risk that the Fed will have to raise rates further than it currently anticipates. But the fact that inflation has ceased to surprise on the upside since the June meeting reduces the risk, in our view, of the Fed becoming even more restrictive in the short term, especially as it is already anticipating only a gradual slowdown in inflation over the coming quarters. Beyond that, financial conditions have been tightening more markedly since June due to rising long rates and falling asset prices, making the Fed's monetary policy more restrictive without the need for further rate hikes.

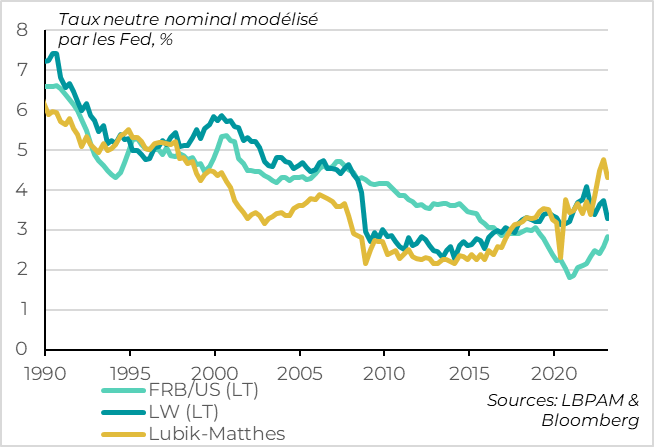

Fig.4 US neutral rate: Fed models agree on upward trend but not on leve

Nominal rate modelled by the Fed, %.

For long rates, there is a broad consensus that rates should be above their pre-Covid level in the next few years, but considerable uncertainty as to their new 'reasonable' level.

This is because in this period of changing economic regimes (inflation, fiscal policy, trade policy, geopolitics, etc.), it is difficult to estimate the equilibrium rate, i.e. the level of rates that will stabilize the economy (what economists call the neutral rate).

The greater persistence of inflation since 2022 and of US growth in 2023 despite the abrupt monetary tightening suggests that this neutral rate is higher than before Covid. But the magnitude of this increase is difficult to estimate.

The models developed by Fed economists to try to extract this neutral rate from the data give widely dispersed results, ranging from a level close to the pre-Covid level (~2.5%) to levels well above 4%. No wonder, then, that disagreements between Fed members over future rates and market rate volatility remain higher than before Covid.

Our central scenario is that the neutral rate is likely to be around 3.5%, compared with 2.5% before Covid, higher than its level since the financial crisis but probably still lower than its level at the turn of the century. Indeed, demographics, declining potential growth and the credibility of monetary policies still argue in favor of structurally limited rates. This is slightly lower than what the market is now thinking (forward rates are currently close to 3.8%). But this is more an indicative level in our minds than a strong conviction.

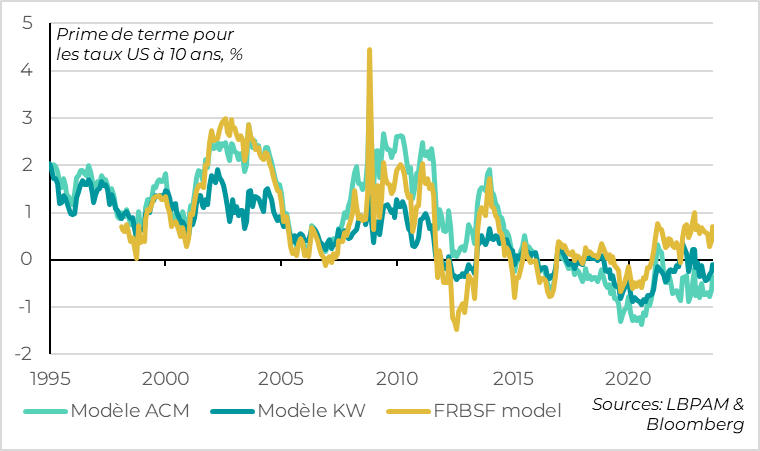

Fig.5 Long vs. short rates: the term premium remains low despite higher risks than before CovidTaux longs vs taux courts: la prime de terme reste faible malgré des risques plus élevés qu’avant le Covid

Term premium for US 10-year rates, %.

ACM model - Model KW - FRBSF model

Beyond the average level of Fed rates in the future, long rates depend on the term premium (i.e., the compensation for holding long-dated bonds and taking a rate risk, compared with holding cash), which is also difficult to estimate and uncertain. Thus, as with the neutral rate, the various models used by the Fed to estimate the term premium indicate widely dispersed values, ranging from -0.5% to 0.75%. Beyond the uncertain level of this premium, what is surprising is that it does not seem to have clearly increased in relation to the pre-Covid period. Yet the return of inflationary risk and clearly less orthodox fiscal policies since Covid argue for a higher risk premium in our view. This may reflect the fact that this premium is usually lower when policy rates are high and geopolitical risk makes safe havens like US debt particularly attractive. But it seems to us that this premium should be a little higher in the future.

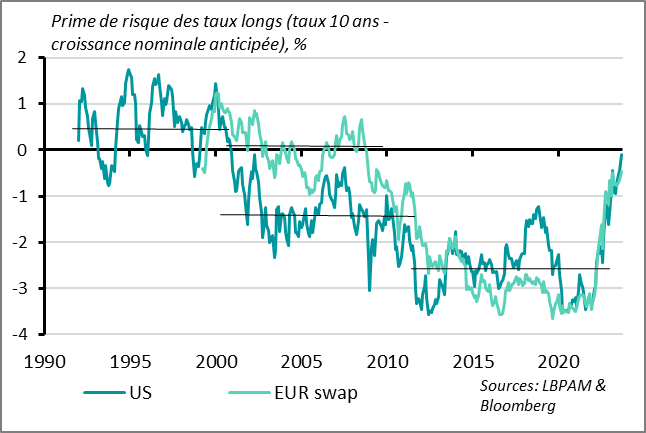

Fig.6 Valuation of 10-year yields: the most attractive since the early 2000s in the United States according to our preferred metric

Long-term interest-rate risk premium (A0year rates - expected nominal growth), %.

All in all, given the uncertainty surrounding the neutral level of rates and risk premiums, we return to a simpler measure for judging the level of rates: the spread between long rates and expected nominal growth. This measure gives an idea of the risk-free remuneration in relation to the average growth of the economy that can be expected. It is comparable to a risk premium. Of course, the 'reasonable' level of this measure changes according to the regime in which the economy finds itself (the 1990s, globalization before the financial crisis, stagnation afterwards...) and its normal post-Covid level is uncertain. But it does at least allow us to compare the level of rates with previous historical periods.

US long yields are back in line with expected growth for the first time since the early 2000s. Even if there is a risk that the reasonable level will be even higher post-Covid, it seems to us that this level is already attractive. We are therefore positive on US long bonds.

The valuation of European long yields has also improved significantly, but remains slightly below its pre-financial crisis level, and below the level of the US yield premium. This leads us to remain more neutral on European rates, preferring shorter maturities.