What will the Fed say about possible rate cuts in 2024?

Link

- The end of the year is approaching, and risk-taking is still alive and well on the markets. Conviction remains strong that a soft landing, particularly in the US, would preserve growth while central banks aggressively ease monetary policy. This week, it's the Fed's turn to open the ball of the last major central bank meetings for 2023. It will be difficult to avoid the question of how much monetary policy easing the market is expecting. In our opinion, apart from staying put, which is widely expected, the message should remain cautious, insisting on the need to maintain a restrictive policy and not mention rate cuts. Nevertheless, the most likely outcome is that inflation will be revised downwards in the projections, along with the outlook for interest rates. This could maintain the dominant economic scenario currently being played out by the market.

- One of the reasons for the Fed's cautious stance is the persistent resilience of the US economy, starting with consumption, itself supported by a labor market that remains robust. In November, 199,000 jobs were created and the unemployment rate fell to 3.7%. Tensions on the labor market persist, as expressed in the acceleration in hourly wages over the past month (+0.4%). This is not entirely compatible with a rapid deceleration in prices towards the Fed's 2% target. Interest rates rose on this news, but equities were buoyed...by the prospect of more growth.

- The situation in the US labor market and rising asset prices, with falling energy prices, have reassured consumers, according to the U. of Michigan's preliminary survey for December. This rebounded strongly, although it remains at a historically low level. More importantly for the Fed, inflation expectations, which had risen sharply over the 1-year and 5-10-year horizons in October, fell back to September levels. The consumer remains the engine of growth, but also the Fed's concern.

- In the Eurozone, finance ministers indicated last Friday that they were close to agreement on new budgetary rules to be implemented in early 2024. Indeed, the suspension of the rules during the pandemic ends at the end of the year. The key reform should be the adoption of greater gradualism in the adjustment of imbalances. This will be a key element in managing the zone's economic cycle. In addition, the European Union will be the first to adopt comprehensive regulations on the use of artificial intelligence. Already, voices are being raised about its overly restrictive nature.

- COP28 is drawing to a close. A final agreement has yet to be reached, particularly on phasing out the use of fossil fuels. As we all know, without a massive reduction in the use of fossil fuels, it will be impossible to prevent the planet's temperature rising by more than 1.5 degrees by the end of the century. On the other hand, COP28 did manage to reach agreement on the creation of a $30 billion fund that could mobilize $250 billion in investment to find climate solutions. In addition, 130 countries pledged to include agriculture in their climate strategies, and 50 oil and gas companies committed to achieving zero methane emissions by 2030.

US growth was one of the surprises of 2023, driven in particular by consumption. As we know, this was partly stimulated by considerable public budget support (close to 2 points of GDP). The strength of this demand has helped maintain a very robust job market, which in turn stimulates household spending.

The employment report for November surprised slightly on the upside. 199,000 jobs were created, compared with the 185 expected by consensus. Even if year-on-year job growth continues to decelerate to 1.8%, this remains a very strong momentum.

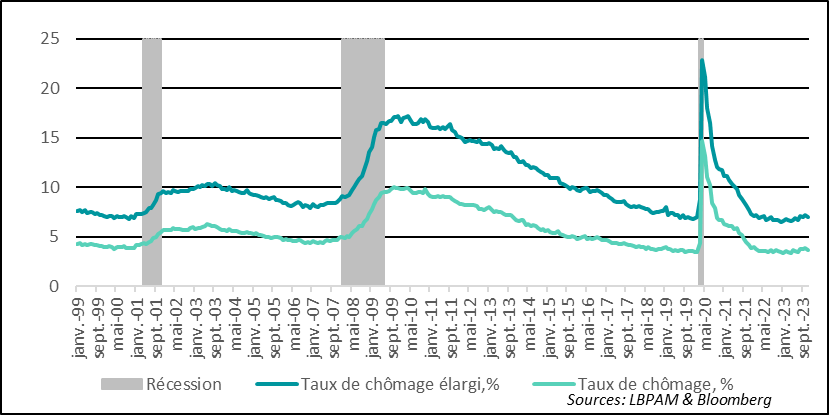

These still abundant job creations translated into a drop in the unemployment rate to 3.7%, down 0.2 points. It therefore remains at a historically low level.

Fig.1 United States: The job market continues to hold, with the unemployment rate reversing its recent upward trend and falling to 3%.

-Recession

-Unemployment rate, %, extended

-Unemployment rate, %.

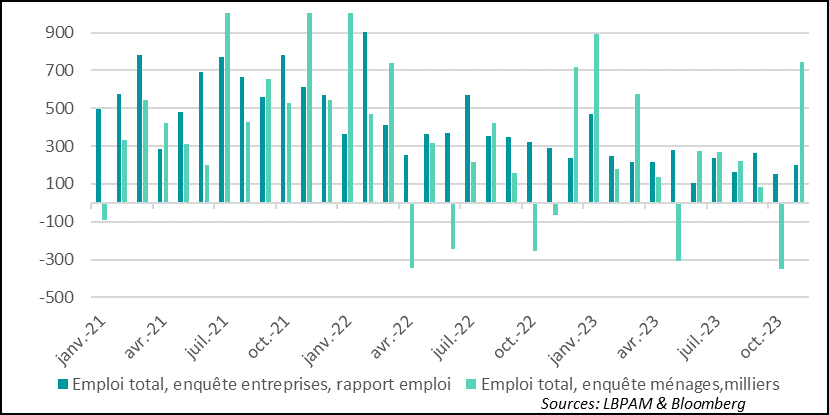

As we all know, statistics on the state of the labor market come from two sources. A household survey and a business survey. Since Covid, the household survey has been a little more volatile than in the past, although it is not uncommon to see very significant movements from one month to the next. The month of November, for example, largely "corrected" the very large gap that had developed between the two surveys.

The household survey showed massive job creation, with over 747,000 new positions created. At the same time, there were 582,000 new entrants to the labor market. The positive difference between job creation and new entrants explains the fall in the unemployment rate.

-Total employment, company survey, employment report

-Total employment, household survey, thousands

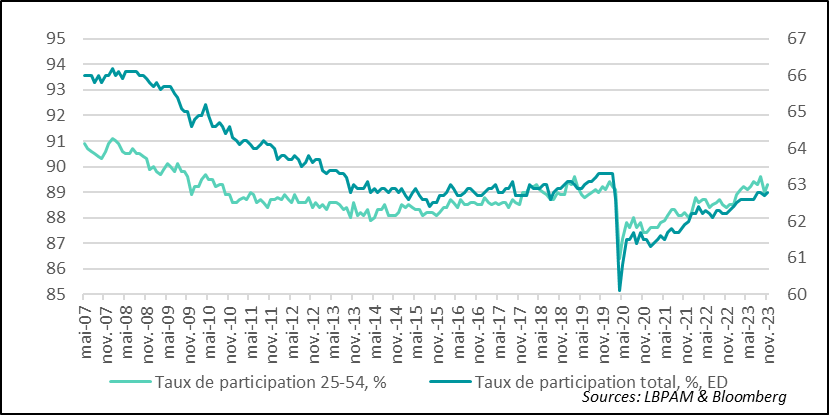

Given this dynamic, the total participation rate rebounded slightly to 62.8, the highest level of the year. Nevertheless, it remains 0.5 points below the pre-pandemic level. On the other hand, the participation rate of the largest cohort, the 25-54 age group, has also rebounded, and remains above the level reached just before Covid.

Fig.3 United States: The total participation rate remains below the pre-Covid level, but for the most important part of the active population it is higher.

-Participation rates 25-54.%.

-Total participation rate, % ED

All these figures are very solid and give the picture of a labor market that remains in very good health.

The business survey which gives the figure being monitored on job creation shows that, with almost 200,000 new jobs created in November, the situation remains very favorable overall.

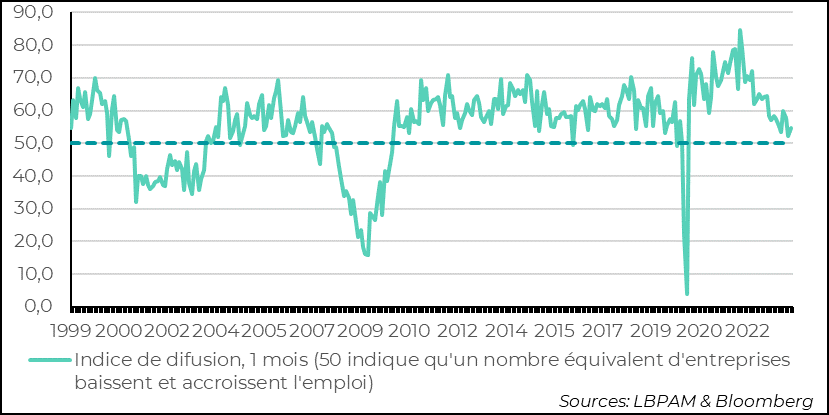

On the other hand, the survey shows that the number of businesses creating jobs has weakened over the course of the year, and obviously since the very strong momentum of 2021-2022. Overall, only just over half of all business sectors (based on 250 sectors) are creating jobs.

Fig.4 United States: The number of sectors creating jobs is falling.

-Diffusion index, 1 month (50 indicates that an equivalent number of companies are downsizing and increasing employment)

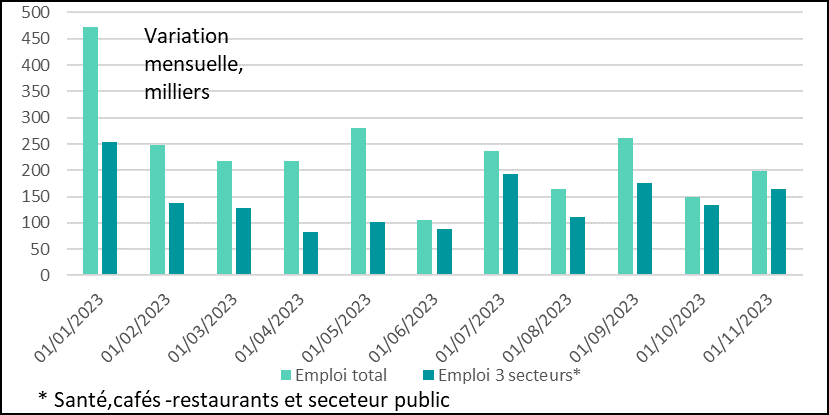

But this also conceals the fact that, in terms of the number of jobs created, they are highly concentrated. In fact, in November, job creations came mainly from three sectors: healthcare, restaurants and the public sector, with over 80% of positions created. The restaurant sector was one of the hardest hit by the pandemic, and has made a long recovery. It has now returned to pre-pandemic levels. The healthcare sector is experiencing a hiring boom. In the public sector, jobs are being created particularly in local government, following massive destruction during the pandemic.

Fig.5 United States: Massive concentration of new job creation in three sectors

-Total employment

-Employment 3 sectors*

*Healthcare, café-restaurants and the public sector

Even if job creation is highly concentrated, the labor market situation remains good.

The downside ohis is that theref t is a risk that wage pressures will persist, complicating the central bank's task of bringing inflation down towards its 2% target.

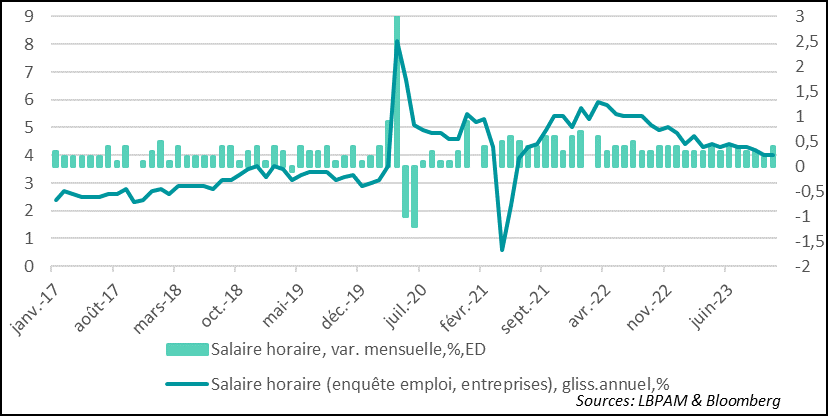

Although the hourly wage statistic derived from the business survey has a number of problems, including that of being disrupted by changes in the composition of the wage bill, it does give us an indication of wage trends.

Unsurprisingly, the still buoyant dynamics of the labor market have boosted wages. Hourly wages rose by 0.35% over the month, after 0.2% the previous month.

Fig.6 United States: Hourly wages accelerated in November to 0.4%, and stabilized at 4% year-on-year.

-Hourly wage, monthly var., %, ED

Hourly wages (emloi survey, companies), year-on-year % change

Wage trends are likely to remain a very important variable for the Fed in its monetary policy decisions. A persistently tight labor market could jeopardize its strategy. For the time being, wages are decelerating, regardless of the measures taken. Nevertheless, the rate of increase remains high. This remains one of the best thermometers for diagnosing the state of the US economic cycle. At this stage, it does not yet appear that overheating in the US economy has been eliminated.

Fig.7 United States: Wage growth eases, but remains incompatible with rapid convergence of inflation towards the 2% target

-Average salary (Atlanta Fed)

-Weekly hourly wage (employment survey, companies

Some people point to the strong productivity figures posted over the last two quarters to reassure themselves that we shouldn't be concerned about sharp wage rises. However, as we all know, productivity statistics are among the most fragile, especially in the very short term. If there is a real productivity shock in the US economy, we won't know for some time. It's not certain that the Fed will take the risk of believing it now.

What we do know, however, is that we have had a multitude of shocks in recent times. The supply shocks have been considerable, notably those linked to covid (bottlenecks in production chains, shortages) or wars (Ukraine-Russia in particular), but the demand shocks linked to public stimulation, notably in the United States, have also been considerable. These shocks are gradually dissipating. The dissipation of supply shocks is the most visible, notably in inflation figures. But demand shocks may prove to be more persistent than some anticipate.