So far the economy has held up well…

Link

The markets are trying to stabilise but remain highly volatile, a sign that the return of confidence will take time. Equities are up slightly on the week, driven by reassuring economic figures and the rebound of Chinese tech. However, banking stocks remain close to their lows of last week, and there is still exceptional volatility in bond yields. Surveys for March suggest that the economy kept its positive momentum in Q1 2023 on both sides of the Atlantic. This is reassuring, given that it had been showing signs of slowing down markedly in the US in late 2022 and was likely to contract this winter in Europe following last summer’s energy shock. Keep in mind, however, that these surveys probably do not fully reflect the shock to banking confidence that has occurred since mid-March. National business surveys in the euro zone in March confirmed the solidity of the economy that PMIs had pointed to last week (the PMI composite had risen by almost 2 points to 54.1). Based on the IFO survey, confidence of German companies, while remaining weak, rebounded to a high since the start of the war Ukraine. In France, an INSEE survey suggested that, while economic activity may have been dented in March by the strikes, the impact is very slight, and companies remain confident for the coming months. In the United States, household confidence improved slightly in March, according to the Conference Board survey, and has held steady on the whole at a high level over the past six months. US households are cautious in their outlook but are still riding a very tight job market. While this is good news for households, it also means that the Fed still has work to do in cooling off an overheated economy. However, monetary figures show significantly slower growth in deposits in the US and loans in the euro zone, a trend that dates back to before the banking stress, which suggests that monetary tightening will be transmitted into the real economy. The question is still: when and by how much. In the US, M2 money supply and bank deposits have shrunk since December on a year-on-year basis for the first time in more than 60 years. This has contributed to banking stress. In the euro zone, growth in money supply and banking deposits remain in positive territory but are slowing at a greater pace than expected. Most importantly, money directly available in the economy (M1) shrank for the first time, and growth in loans slowed, so much so that lending’s contribution to growth moved into negative territory in February. These figures back our scenario of weak growth for the coming quarters, as monetary policies are tightened to cool off demand and, hence, to limit inflationary pressures. The risk now is that banking stress will exacerbate these recessionary pressures massively, but this is not our baseline scenario as things now stand.

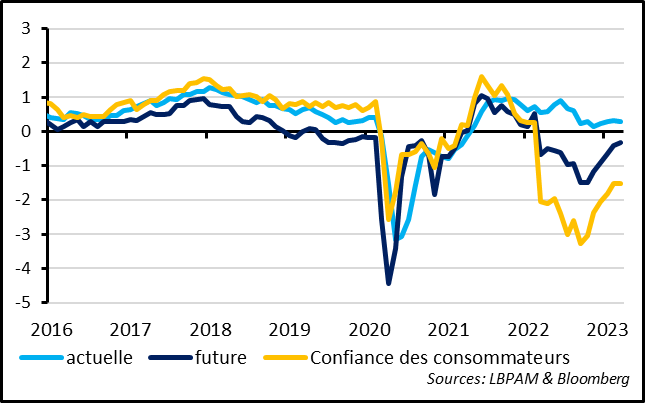

Fig. 1 Euro zone: Companies continue to report slightly stronger activity in Q1 and a return of confidence in their guidance

Companies’ confidence continued to improve in March, according to national surveys, in accordance with the surge in the euro zone PMI composite (+2 points to 52.6). Although these surveys probably do not yet reflect the impact of March’s financial stress on companies’ guidance, their good health and confidence during Q1 is reassuring, while investor and consumer confidence declined slightly this month.

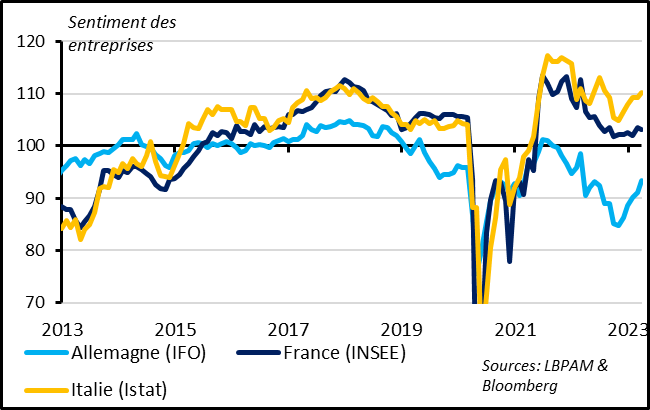

Fig. 2 Euro zone: German companies are less pessimistic, while French and Italian companies remain optimistic

Unexpectedly and in contrast to the ZEW, the German IFO survey improved further in March but remains rather low. This improvement occurred across all sectors and in both current conditions and companies’ future expectations The best leading indicator of the German economy, manufacturer expectations, for example, continued to recover and in March hit a high since the start of the war in Ukraine.

The INSEE survey shows that French companies’ confidence declined only slightly in March after rising sharply in February and remains above its historical average. While the strikes have squeezed French companies’ activity a bit, the impact has been very limited and has not kept them from projecting an increase in activity and employment in the coming months in both manufacturing and services. Note, however, that the number of manufacturing companies planning to raise their prices in the coming months stopped declining in March and remains at a level that had not been seen since the early 1980s, until the Covid crisis.

Figures from the Italian statistics office suggest that confidence of both companies and households has continued to improve in March and is once again at levels consistent with reasonable growth in economic activity.

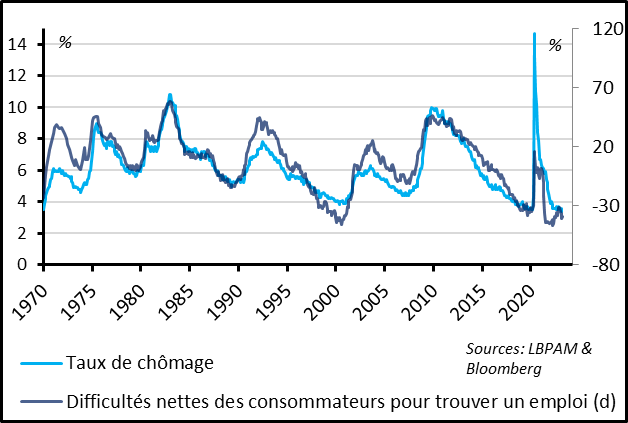

Fig. 3 United States: Household confidence remains solid, thanks to the continued robust job market

US consumer confidence remained solid in March, according to the Conference Board survey. While US households have been cautious in their outlook since last year, they continue to report that their present situation is very good, despite still-high inflation. This is due to the exceptional strength of the job market. For example, the ratio of “jobs plentiful” to “jobs-hard-to-get” declined only slightly in March and remains near its all-time highs, after rebounding over the past three months. This is consistent with an unemployment rate that would remain close to its lows, at 3.6% in March. This is good news for households, who are riding strong upward momentum in wage income and confidence in job security. But it’s not good news for the Fed, as an overheating job market could exert steady pressures on wages and, ultimately, on inflation. That’s why the Fed remains committed to slowing the economy, at least for as long as the risk of a systemic shock remains under control.

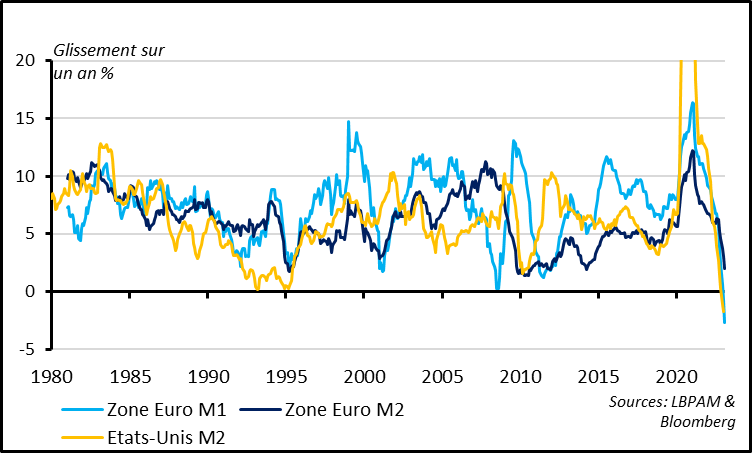

Fig. 4 Euro zone: The impact of monetary tightening began to show up in monetary aggregates even before the banking stress of March

Growth in money supply slowed more than expected in February in the euro zone, from 3.5% to 2.9% on a year-on-year basis, to a low since 2014, a sign that monetary tightening is gradually being transmitted to the financial sector.

The most liquid component of money supply, M1 (in short, money in circulation and sight deposits) even shrank for the first time in more than 40 years, by -2,7%. Historically, this is a good leading indicator of the economic picture, as it shows the quantity of money that households and companies can spend directly in the economy. This decline is even greater when factoring in high inflation, suggests that demand is likely to slow considerably in the coming quarters.

Keep in mind, however, that monetary shifts have an unpredictable impact on economic activity, in terms of both timing and extent, especially when liquidity remains abundant from past injections. The monetary situation is less exceptional in the euro zone than in the US, where there has been no contraction in any money supply components (not just M1) or deposits in the real economy. In the euro zone, the shrinking in M1 is due in part to transfers of sight deposits into higher-earning term deposits, which are included in M3 but not in M1. These transfers make banks’ financing more expensive but do not reduce their liquidity. Moreover, money-market funds compete less with banks in attracting liquidity in the euro zone than in the US, and we therefore believe that euro zone bank liquidity risk is lower in the euro zone than in the US.

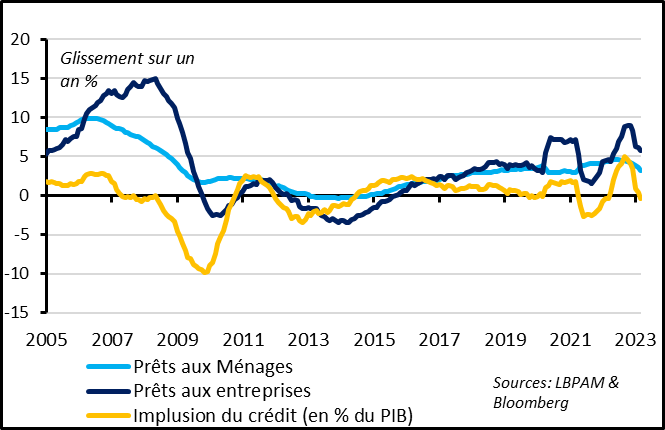

Fig. 5 Euro zone: The slowing of household and corporate lending is beginning to weigh on economic activity

A more direct way to assess the impact of monetary tightening on economic activity is to look at lending to the real economy, which has slowed considerably in the euro zone since the end of 2022. Even before the recent banking stress, monetary tightening was causing a slowdown in lending, which was going to weigh on economic activity in the coming months.

Lending to companies and households still rose by, respectively, 5.7% and 3.2% year-on-year in February. This is relatively high in itself but is still a significant slowdown from their 2022 increase. In reality, lending to companies has declined slightly over the past four months.

All in all, lending’s contribution to GDP growth, known as the credit impulse, became (slightly) negative in February after having been far into positive territory in 2022.

Our scenario had already assumed that lending would have a negative impact in the coming quarters, causing a slight recession in the US and keeping growth at a low level in the euro zone. This is what central banks want to do when they raise their rates and reduce liquidity, in order to slow demand and get inflation back under control. However, this must not trigger a systemic shock to the financial system, as that would curtail lending and shrink the money supply abruptly and cause a depression.

Sadly, the process of monetary tightening rarely (if ever) goes off smoothly, as we are now seeing, especially after a long phase of zero interest rates and abundant liquidity. We don’t see much systemic risk arising from the current banking stress, but we also believe that other financial incidents are likely in this environment of higher rates and withdrawn liquidity.